Part 2 of 2

DEMOLITION WORK

Observing events from across the border, Indians could perhaps be excused for indulging in that malicious enjoyment of another’s misfortunes known as Schadenfreude. While Pakistan was being bombed and burned, ‘lethargic, underfed’ India, though itself beset by countless insurgencies and a major identity crisis, was somehow being reincarnated as a potential superpower. Pakistanis, of course, saw these developments as connected. They suspected all manner of unholy but well-funded alliances between RAW, the Indian intelligence service, and their own dissident elements – Sindhis, Baluchis and mohajirs as well the mainly Pathan mujahidin. They also noted New Delhi’s close relations with the NATO-backed Karzai government in Kabul. A 2005 Indo-US agreement to exchange civil nuclear technology heightened Pakistan’s sense of international isolation, while the growing presence in Afghanistan of Indian counsellors, technocrats and corporate investors revived the spectre of encirclement. Bhutto’s ‘defence in depth’ had become a sick joke, Zia’s ‘defence in Islam’ likewise.

Though little acknowledged in Delhi, there were, however, other grounds for supposing that developments in India had contributed to the crisis in Pakistan. For just as most Indians liked to imagine that Pakistan was finally paying for the presumption of Partition, most Pakistanis detected confirmation of the fear that had led to Partition in the first place – namely that an independent India would degenerate into a ‘Hindu raj’ with Muslims there becoming second-class citizens. This perception owed everything to the sensational rise in India’s political firmament of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), together with the outrages and atrocities that accompanied it and an Indian military offensive in Kashmir that was partly informed by it.

Back in 1988 the prospects for Indo-Pak bilateral relations had seldom looked brighter. In Rajiv Gandhi, Benazir Bhutto and Dr Farooq Abdullah (son of Sheikh Abdullah, the ‘Lion of Kashmir’) a new generation of more photogenic leaders approached the Kashmir conundrum minus all the hardline baggage of their parents and at the head of comfortable majorities in their respective national and state assemblies. Their relations were cordial and their first exchanges promising. Only the timing was wrong. In Kashmir the recent victory of Farooq Abdullah’s National Conference/Congress coalition in the state elections had benefited from outrageous vote-rigging and been hotly challenged by the opposition Muslim United Front. Failing to win redress, and so despairing of Indian democracy, some of the Front’s more militant supporters had then crossed into Pakistan in search of arms and support for the campaign of terror that began the following year.

Meanwhile in India, the nation was being held hostage by its television sets. In 1987 the state broadcaster had begun relaying a lavishly dramatised serialisation of the Ramayana. Broadcast of a Sunday, it ran to seventy-two episodes, lasted a year and a half and was watched by an unprecedented 80 million viewers. Cities fell silent, lunch went uncooked and markets were deserted as each screening took on the sanctity of an act of worship. Sets were garlanded for the occasion; sales and rentals rocketed. India was discovering not just the joys of family viewing but the excitement of a wider, more contentious identity. Muslims viewers were said to be equally entranced, but among those who thought of themselves as Hindus this TV rendering of an epic of uncertain provenance, many recensions and questionable historicity acquired nearcanonical status. More scripture than catechism, it served to define Hindu values and instil a sense of India as one great Ram-worshipping Hindu congregation. Ram himself was elevated above other avatars of Lord Vishnu, and attention then turned to such snippets as tradition preserved of his possible place in history.

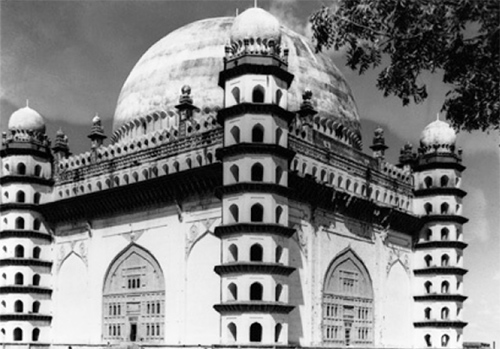

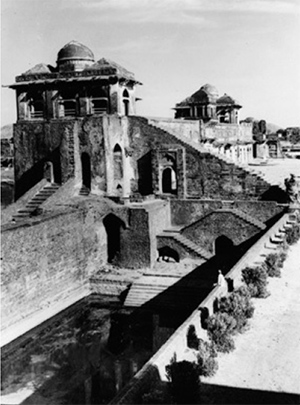

Ayodhya in UP is mentioned as the site of his capital; and there, according to a later local tradition, beneath a Mughal mosque built on the orders of Babur to celebrate the Muslim triumph over India’s idolators, lay the actual ground (the Ramjanmabhumi or ‘Ram’s-life-giving-earth’) where Lord Ram had been born. A small and suspiciously recent image of the baby Ram within the Baburi (or Babri) mosque marked the spot. But the mosque was locked and no longer in use, preventing access to this shrine. Then in 1986, at the behest of a World Hindu Council (VHP) demanding Lord Ram be liberated from his ‘Muslim gaol’, the locks had been opened. Coming hard on the heels of the Shah Bano decision placating Muslim orthodoxy, it looked as if Rajiv Gandhi’s government now sought to placate Hindu radicalism. Primed by this success and emboldened by the impact of the TV series, the VHP and its affiliates (including the paramilitary RSS and the vote-hungry BJP) scented a once-in-a-century opportunity.

The BJP, a reincarnation of the post-Independence Jan Sangh and the pre- Independence Mahasabha, had seldom won more than a handful of seats in a national election. But in 1989 its tally shot up to 86 with 11 per cent of the vote, in 1991 to 120 with 20 per cent of the vote, and by the late 1990s it had increased to 25 per cent of the vote and enough seats to head a coalition government in New Delhi. The agitation over the Babri mosque was the making of the party. For though the VHP led the cry for the mosque to be replaced with a gleaming new temple, it was the BJP’s leaders, especially L. K. Advani and A. B. Vajpayee, who capitalised on the issue.

In the run-up to the 1989 elections, BJP men were prominent in a campaign to fund and consecrate bricks from all over north India for the construction of the proposed temple. The ‘bring-a-brick’ ceremonies triggered serious Hindu- Muslim strife and massacres in Bihar, but they won the BJP support among TV-savvy middle-class voters thoughout the populous north. A year later, Advani upped the stakes by staging a rath yatra, a chariot procession, from Somnath in Gujarat (where a magnificent new temple had lately been built to replace that destroyed by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1025) to Delhi, Bihar and Ayodhya. The chariot, a Toyota utility van festooned in saffron and customised to resemble the prehistoric wagons seen on TV, wound its way amid massive crowds to Delhi. When the new government, a coalition National Front, failed to stop it, it continued on, leaving in its wake more riots and massacres. Advani was eventually arrested by the anti-BJP government in Bihar and the cavalcade itself was halted by its counterpart in UP. But enough fanatical ancillaries reached the Ayodhya site to give the security forces a tough battle and provide the movement with its first martyrs.

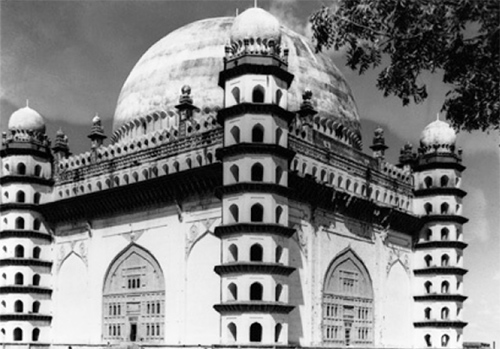

In December 1992 the BJP leaders headed for the Babri mosque yet again, this time to attend a foundation-laying ceremony for the proposed new temple. By now the VHP had acquired some adjacent land and had poured a certain amount of concrete, all in contravention of a standstill court order that UP’s new BJP government declined to enforce. Emboldened by the state government’s apparent sympathy and unimpressed by Delhi’s efforts to have the matter referred to the Supreme Court, 100,000 saffron-clad zealots turned up for the ceremony on 6 December. According to the BJP, things then got out of hand; according to a later inquiry, the BJP leaders had ensured that they would.7 The flag-waving mob scaled the mosque’s protective railings and then the mosque itself. Picks, sledgehammers and grappling irons materialised. As the mosque’s three Mughal domes came crashing down in a tableau worthy of Goya, the foundation-laying ceremony degenerated into a demolition spectacle. The state police had fled; 20,000 troops stationed near by were not even summoned. The wreckers rounded off their day by torching Muslim homes in the vicinity.

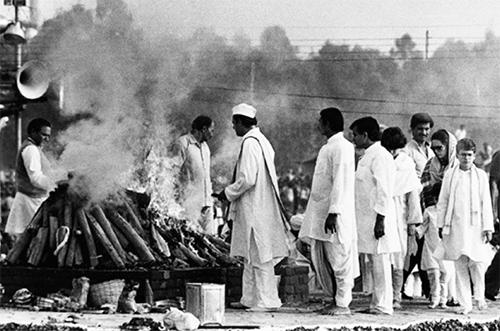

Courtesy of the media, the events in Ayodhya instantly excited such Hindu triumphalism and Muslim resentment that ‘communal rioting’ – a euphemism for sectarian atrocities – broke out right across northern and central India on a hitherto unprecedented scale. Muslims were more often the victims than the perpetrators. Of the 800 massacred in Bombay’s ‘riots’, two-thirds were Muslims. There and elsewhere Muslims would strike back, targeting the police and national institutions like the Stock Exchange and the metropolitan railway. But they risked a greater retaliation. The worst came in Gujarat in 2002 when a train carrying ‘pilgrims’ back from Ayodhya caught fire as it left Godhra station. The fire claimed fifty-eight lives, and because the passengers had used the halt to abuse local Muslim vendors it was assumed to be a case of retaliatory arson. The retribution that followed left less room for doubt. All over southern Gujarat death squads sallied forth to dispossess, maim, rape and murder Muslims. With a BJP government in power in Delhi and another in power in the state, the victims felt especially vulnerable. At least 2000 died horribly, with many more losing limbs, virginity, property and livelihoods. As in Delhi during the pogrom of Sikhs in 1984, officials reportedly aided the destruction by distributing electoral registers, the police had orders to make themselves scarce and government ministers took over control posts to orchestrate the attacks.

Eight years later, a bandannaed gunman in Bombay’s Taj Hotel was asked by one of his hostages why he was about to kill them all. He reportedly replied: ‘Have you not heard of Babri Masjid? Have you not heard of Godhra?’ Then he opened fire.

The demolition of the Babri mosque, the massacres that followed and the state’s complicity in them antagonised all South Asia’s Muslims, whether mujahidin or moderates, Sunni or Shi’i, Indian, Kashmiri, Pakistani or Bangladeshi. Comparisons were again drawn with the dreadful events of Partition. But few paused to consider how the logic of the BJP’s demand for Hindutva, or ‘Hinduness’, merely mirrored that of Jinnah’s two-nations theory. BJP ideologues insisted that in the name of secularism the Indian state had been appeasing Muslim sentiment for too long; for India to realise its potential it needed to reject such policies and embrace and assert its overwhelming ‘Hinduness’; Muslims and Christians had dominated the country’s past by dividing and oppressing Hindus; it was time for the Hindu nation to reunite, rediscover its prior identity and its glorious heritage, and take pride in celebrating them; non-Hindus merited only suspicion and must accept a subordinate status. All of which, after juggling ‘India’ for ‘Pakistan’ and ‘Muslim’ for ‘Hindu’, could have come from the textbook of Jinnah’s Muslim League.

Liberal opinion in India was also horrified. In the English-language press the Babri affair was portrayed as the greatest ever threat to the state, worse even than Mrs Gandhi’s Emergency or the Chinese incursion. For as of 1992 India could no longer call itself a secular nation. The dark forces of sectarian conflict had been unleashed, the noble legacy of Gandhi and Nehru rejected. The state was irrevocably tainted with the bigotry it had so long decried. Intellectual and press freedom would suffer – and did – under the BJP’s chauvinist rule. And the political process that had brought that party to power seemed itself thereby discredited. One by one, the founding principles of the nation were falling. Socialism had died in the 1970s, secularism was expiring in the 1990s and democracy looked doomed by association.

But to Muslim minds secularism was just a red herring. They had no more time for it than did the BJP. To their way of thinking the main casualty of the Babri affair was not some suspect Western liberal value but Islam, their lifeforce and their identity. In the cities of Pakistan every anti-Muslim outrage in India brought thousands on to the streets and swelled the ranks of the jihadist lashkars. The mujahidin in Kashmir became national heroes. Outbidding one another in their promises of support, the civilian governments of Benazir and Sharif brazenly countenanced the despatch of Pakistani volunteers to stiffen the resolve of the Kashmiri ‘freedom-fighters’.

There, in Indian-held Kashmir, the liberationist movement prompted by the vote-rigging of 1987 and the 1989 dismissal of Farooq Abdullah’s government had taken both Delhi and Islamabad by surprise. Electoral malpractice had seemingly achieved what forty years of Pakistani prompting and Indian provocation had failed to elicit – a militarisation of the Kashmiris themselves. Self-determination was initially the goal, but in the early 1990s, as the BJP ramped up its rhetoric in India and jihadist lashkars in Afghanistan were redirected to Kashmir, the struggle turned increasingly sectarian. The liberation movement was subsumed in a jihadist bloodbath. Mujahidin targeted the Valley’s Hindu minority, hundreds of whom were horribly massacred while most of the remainder were removed to safety. With the state now under President’s Rule, the exodus was organised by Kashmir’s controversial governor, a man associated with Sanjay Gandhi’s excesses during the 1975-7 Emergency who had been despatched to Kashmir in 1989 by a Delhi government that included the BJP and who would later himself join the BJP.

The impression that India was clearing the decks for action in Kashmir was heightened by the despatch of ever more troops. Following a Pakistani infiltration of the Line of Control near Kargil (between Srinagar and Leh) in 1999 – itself a test of whether Pakistan’s recently demonstrated nuclear capability was insurance against a disproportionate Indian response – the number of Indian troops in Kashmir approached half a million. The Valley was now clearly under military occupation, and if not technically a war zone was certainly a ‘dirty war’ zone. One of the main reasons for India’s claiming Kashmir in the first place – to demonstrate the secularist credentials of the Indian republic – had become as redundant as secularism itself. Hindu fundamentalism and Islamic fundamentalism were feeding off one another. ‘The two processes began independently, yet each legitimised and furthered the other.’8

In 2001 ‘Kashmiri terrorists’ mounted an attack on the state assembly in Srinagar, then followed it with an attempted suicide bombing of the Indian parliament in New Delhi. Neither succeeded, and the latter, a murky affair involving a one-time Indian informer, raised questions that have yet to be answered. Together they occasioned an eruption of national outrage, followed by warlike deployments along the Pakistan frontier that came to nothing. But perhaps it was the terrorists’ targets that were most instructive. Chosen for maximum impact, they yet hinted at an ongoing grudge against electoral mismanagement as much as the nation responsible. A year later the state elections in Kashmir went ahead regardless. Generally reckoned fair and well organised under the circumstances, they attracted a surprising 48 per cent of voters. Subsequent polls improved still further on this. Though the bombings and shootings continued, Kashmiris had clearly not given up on the democratic process.

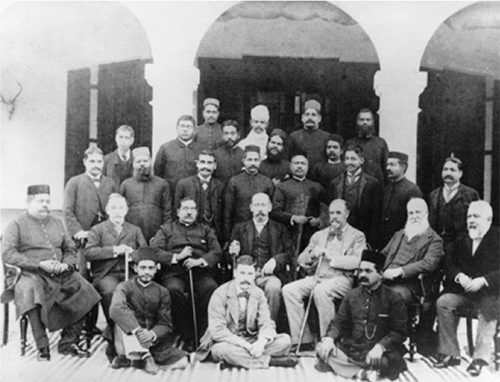

Nor had the governments of India and Pakistan given up on improving their bilateral relationship. Despite war scares over Kargil in 1999, the attack on the Indian parliament in 2001 and the terrorist rampage through Bombay in 2008, both governments fitfully pursued a normalisation of relations. Of all people it was Prime Minister Vajpayee of the first BJP-led government in Delhi who in 1999 epitomised the launch of these overtures with a well-publicised visit to Lahore to meet Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. International pressure following the previous year’s nuclear tests played its part in the meeting; nothing substantial was achieved; and the Kargil incursion seemed to scupper further progress. But in 2001 Vajpayee welcomed a return visit, this time of Musharraf who had by then taken over as president of Pakistan. Again little was achieved. But later in the year the events of 9/11 and Washington’s re-engagement in Afghanistan revived what was now being called a ‘process’. Under American pressure to end Pakistan’s support of the mujahidin, Musharraf needed a face-saving quidproquo of talks on Kashmir; and Vajpayee, needing something to show for his previous efforts, was prepared to have one last go.

Thus direct dealings were resumed in 2004 at a heads-of-state meeting of the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC), a body set up in the days of Rajiv and of the Indian involvement in Sri Lanka that had led to his 1991 assassination. Political progress remained minimal. But the setting did encourage confidence-building agreements on cultural contacts, travel links, social concerns and anti-terrorism measures. Above all, the enormous potential of regional trade and economic development was recognised in a commitment to establish a South Asian Free Trade Area.

Expectations of what might yet become the world’s most populous trading group have still to be realised. On the other hand, the impact of globalisation and of India’s growing economic clout had at last entered the bilateral equation. Optimists hoped that Delhi’s new-found confidence promised an end to its obsession with Pakistan. Prosperity, whether feared or shared, could conceivably trump political intransigence; and, sixty years on, the conundrum that is Kashmir could yet be laid to rest by an Indian-led surge in cross-border trade, investment and collaboration. Pessimists might retort that with Pakistan looking ungovernable, Bangladesh looking submersible and both of them mired in postmilitary recriminations, the outlook for regional co-operation could scarcely be bleaker. Yet if recent history is anything to go by, all such forecasts merely invite contradiction. Expect the unexpected.

Though the great turnaround in India’s economic fortunes had become selfevident by the turn of the century, it had not been at all widely foreseen. Nor for that matter is it easily explained. The gradual deregulation of the economy and the enthusiasm with which the Indian private sector, both at home and abroad, embraced the opportunities of globalisation were undoubtedly critical. So too were India’s vast human resources; thanks to the industrialisation and language policies of the Nehru era, Midnight’s grandchildren outnumbered any other modestly remunerated but technically proficient English-speaking generation in the world. The West’s earlier outsourcing of its technology, economic thinking and favoured language had made possible India’s insourcing of the West’s service industries.

Necessity, too, played its part. By 1991 India’s financial deficit, accumulated over decades of state-run inefficiency, had threatened to bring the country to a standstill. The national debt topped $70 billion and foreign exchange reserves were sufficient for just two weeks. Narasimha Rao, the Congress prime minister who had just replaced Vajpayee, had little choice but to invite his chosen finance minister, Manmohan Singh, to embrace the market. Although Rajiv Gandhi, A. B. Vajpayee and others had got the engine of reform started, it was Rao and Singh who released the handbrake of state control and let private enterprise run riot.

Less obviously, a variety of social and political factors provided a context and climate in which the reforms could thrive. One such was a gradual restoration of the federalist principles enshrined in the original constitution. Rajiv Gandhi, though no great thinker, had concluded from the turmoil of his mother’s later years that government had become too interventionist. The people and their elected representatives had grown accustomed to looking to the state for every imaginable provision and facility. It was time they rediscovered their own potential through the exercise of private initiative, local endeavour and personal responsibility. In terms of the economy this had meant a first tentative simplification of the licensing raj with a reduction of tariffs, the freeing of some quotas and a little encouragement for private investment. At the grass-roots level it led to the revival of locally elected bodies that could be entrusted with community responsibilities, plus the funds to perform them. And at the constitutional level it led to a reining in of the central government’s propensity for interfering in the states.

The circumstances under which President’s Rule might be imposed were more closely defined, legislation was introduced to discourage elected representatives from changing their party allegiance whenever the inducements of office, cash or concessions directed, and efforts were made to provide state governments with a more equitable share of federal revenues. States run by governments that were of the same party as that in power in Delhi still tended to be better funded than others, and centre-state tensions were by no means reduced. But with post-electoral digvijayas like that conducted by Mrs Gandhi becoming a thing of the past, state governments enjoyed greater stability and generally responded by behaving more responsibly. Instead of pandering to New Delhi, they increasingly competed with one another to attract investment, improve infrastructure and, in the best cases, extend social provision.

These trends anticipated a wider decentralisation of the political process and encouraged a dramatic maturation of Indian democracy. Rajiv Gandhi’s landslide victory in 1984 would not be repeated. In fact the one-party domination by Congress became the exception rather than the rule as minority governments, multi-party coalitions and electoral fronts trooped through the corridors of power in Delhi. In some states Congress became an irrelevance, in others it survived through local alliances. Everywhere it was parties based on caste allegiance, sectarian sentiment and regional or linguistic solidarity that were in the ascendant. Instead of simply deciding between Congress or a non-Congress party of one’s choice, voters now encountered a great electoral bazaar stocking a political style to suit every identity. In reflecting the numerical balance of Indian society as well as its diversity, the bazaar naturally empowered those parties identified with the hitherto uncultivated masses that comprised the lower castes and the Dalits (Harijans, outcastes). This was especially evident in the great northern states of UP and Bihar where, by 2000, the votes of Dalits and Yadavs were consistently returning caste-based governments pledged, above all, to uplifting their own communities. As chief minister of UP, the formidable Ms Mayawati of the (Dalit) Bahujan Samaj Party ordained Dalit theme parks and festooned the state with statues of distinguished Dalits, herself among them.

Not everyone approved. A degeneration in standards of political conduct was widely remarked and often attributed to these new caste-based parties. Studying a 2004 analysis of the affidavits filed by elected MPs, Ram Guha reports that 35 per cent of the (Yadav) Rastriya Janata Dal members and 27 per cent of the (Dalit) Bahujan Samaj Party members confessed to having once faced criminal charges. The Congress party and the Hindu nationalist BJP fared slightly better with 17-20 per cent having faced criminal charges. Yet to judge by the assets and loans the latter saw fit to declare, members of these two mainstream parties had much stickier fingers. For a Congress member, assets of 31 million rupees were the average. ‘We may conclude’, says Guha, ‘that, while in power, the Congress and BJP have systematically milked the system.’9

With the Delhi parliament sitting for no more than seventy or eighty days a year and seldom well attended, it could be argued that a decline in the probity of its members and in the quality of debate scarcely mattered. Legislation was preapproved behind closed doors, parliament’s job being simply to pass it. Getting elected was what mattered; and what with by-elections, state elections and local elections providing an almost continuous commentary on the political scene, the counting of ballots had become a constant of political life.

But by the same token India’s democracy could not be considered unresponsive. If it empowered the underprivileged and inducted the hitherto under-represented, then that surely was what democracy was all about. The exigencies and expenses of office, whether above-board or not, generally had a sobering effect. The chauvinism of the BJP had sent shivers down secular spines in the early 1990s, but in government the party, though obdurate in matters dear to its heart, proved far from irresponsible. Likewise Kashmir’s unimpeded participation in the electoral bazaar increased hopes for a solution to South Asia’s most intractable problem. In 2010, with elected governments once again in power in all the successor states of pre-Partition India, democracy looked far from doomed. Arguably its promise of a better tomorrow was never brighter.

India A History, by John Keay

48 posts

• Page 5 of 5 • 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Re: India A History, by John Keay

SOURCE NOTES

Publication details of most of the cited works will be found in the bibliography. The following abbreviations refer to works listed in the General section of the bibliography: CEHI – The Cambridge Economic History of India, vol.1, c1200-c1750 (ed. Raychaudhuri, T. and Habib, I.) HCIP – The History and Culture of the Indian People (ed. Majumdar, R.C. et al) HOIBIOH – The History of India as Told by its Own Historians (ed. Elliot, H.M. and Dowson, J.) NCHI – The New Cambridge History of India (ed. Johnson, G. et al)

INTRODUCTION

1 Majumdar, R.C., in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’ p.47

2 Keay, J., India Discovered, HarperCollins, London, 1988

3 Stein, B., A History of India, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998, p.5

4 Braudel, F. (trans. Maine, R.), A History of Civilisations, Penguin, New York, 1993, p.217

CHAPTER 1

1 Adapted from the Satapatha Brahmana as rendered by A.D. Pusalkar, in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’, pp.271–2

2 Thapar, R., ‘The Study of Society in Ancient India’, in Ancient Indian Social History, p.212

3 Bhandarkar, D.R., quoted in Possehl, G. (ed.), Harappan Civilisation, p.405

4 Allchin, B. and F.R., Birth of Indian Civilisation, p.131

5 Ibid, p.132

6 Ghosh, A., The City in Early Historical India, p.83

7 Lal, B.B., ‘The Indus Civilisation’, in Basham, A.L. (ed.), A Cultural History of India, p.16

8 Pusalker, A.D., in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’, p.181

9 Ratnagar, S., Enquiries into the Political Organisation of Harappan Society, p.152

10 Ratnagar, S., Encounters: The Westerly Trade of the Harappan Civilisation, p.247

CHAPTER 2

1 Thapar, R., ‘The Image of the Barbarian in Early India’, repr. in Ancient Indian Social History, p.140

2 Thapar, R., ‘The Study of Society in Ancient India’, repr. in ibid, p.190

3 Asiatick Researches, vol.1, 1788, quoted in Keay, John, India Discovered, p.30

4 Muller, F. Max, Chips from a German Workshop, vol.1, 1867, p.63

5 Wheeler, R.E. Mortimer, ‘Harappan Chronology and the Rig Veda’, repr. in Possehl, G.L. (ed.), Ancient Cities of the Indus, p.291

6 Dales, G.F., ‘The Mythical Massacre at Mohenjo Daro’, repr. in ibid, p.293

7 Elphinstone, Mountstuart, The HistoryOf India etc., p.54

8 Majumdar, R.C., Ancient India, p.30

9 Ghosh, B.K., ‘Language and Literature’, in ‘The Age of the Rik-Samhita’, bk v in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’, pp.347-8

10 Rig Veda, Mandala I, 175

CHAPTER 3

1 Kosambi, D.D., The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline, p.89

2 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, p.2

3 Ibid, p.146

4 Ghosh, A., The City in Early Historical India, p.34

5 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, pp.16-17

6 Quoted in Meyer, J.T., Sexual Life in Ancient India

7 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, p.22

8 Ibid, p.134

9 Sharma, J.P., Republics in Ancient India, p.9

10 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, p.73

11 Ghosh A., The City in Early Historical India, p.64

12 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, pp.102-3

13 Rig Veda, X, 90

14 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, p.170

15 Spelman, J.W., Political Theory of Ancient India, p.69

CHAPTER 4

1 Mountbatten, quoted in Collins, L. and Lapierre, D., Mountbatten and the Partition of India, p.70

2 Lane Fox, R., Alexander the Great, p.56

3 Marshall, J., Taxila, vol.1, p.12

4 Basham, A.L., The Wonder that was India, p.390

5 Bechert, H., in When did the Buddha Live?: The Controversy of the Dating of the Historical Buddha (ed. Bechert, H.), p.286

6 Sharma, J.P., The Republics in Ancient India, pp.123-4

7 Mookerji, R.K., in HCIP, vol.2, ‘The Age of Imperial Unity’, p.25

8 Thapar, R., A History of India, vol.1, p.59

9 Majumdar, R.C., Ancient India, p.101

10 Lane Fox, R., Alexander the Great, p.331

11 Mookerji, R.K., in HCIP, vol.2, ‘The Age of Imperial Unity’, p.44

CHAPTER 5

1 Asiatick Researches, 1793, quoted in Keay, J., India Discovered, p.35

2 Wells, H.G., A Short History of the World, 1922, repr. Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1946, p.114

3 Kautilya (ed. and trans. Rangarajan, L.N. etc.), The Arthasastra, p.21

4 Trautmann, Thomas R., Kautilya and the Arthasastra, p.186

5 Fergusson, J., A History of Indian Architecture, London, 1897

6 Yazdani, G., The Early History of the Deccan, vol.1, p.69

7 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History …, 1975, preface and pp.17–53

8 Tod, James, Travels in Western India, W.H. Allen, London, 1839, p.76

9 Prinsep, James, in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol.8, 1838, quoted in Keay, John, India Discovered, p.53

10 As trans. in Thapar, Romila, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, p.256

11 Mookerji, R.K., ‘Asoka the Great’, in HCIP, vol.2, ‘The Age of Imperial Unity’, p.74

12 Wells, H.G., A Short History of the World, 1922, repr. Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1946, p.115

13 Kautilya (ed. and trans. Rangarajan, L.N. etc.), The Arthasastra, p.741

14 McCrindle, J.W., Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian, Trubner, London, 1877, p.84

15 As trans. in Thapar, Romila, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, p.254

16 Ibid, p.266

17 Thapar, R., ‘Asokan India and the Gupta Age’, in Basham, A.L. (ed.), A Cultural History of India, p.42

CHAPTER 6

1 Narain, A.K., The Indo-Greeks, p.viii

2 Kulke, H. and Rothermund, D., A History of India, p.83

3 S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha, A Comprehensive History of India, vol.2, The Mauryas and the Satavahanas, p.102

4 Thapar, Romila, A History of India, vol.1, p.93

5 Narain, A.K., The Indo-Greeks, p.11

6 Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, p.70 7 Bagchi, P.C., India and China: A Thousand Years of Cultural Relations, p.10

8 Dani, A.H., Human Records on the Karakoram Highway, p.49

9 Ibid, p.77

10 S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha, A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar, 1955, p.130

11 Hart, George L., ‘Ancient Tamil Literature: Its Scholarly Past and Future’, in Stein, Burton (ed.), Essay son South India, pp.41-2

12 Maloney, Clarence, ‘Archaeology in South India: Accomplishments and Prospects’, in ibid, p.24

13 Wheeler, R.E. Mortimer, Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontiers, p.147

14 Glover, I.C., Early Trade Relations Between India and South East Asia, pp.47-8

15 Coedes, G., The Indianised States of Southeast Asia, p.18

16 Quoted in Sarkar, H.B., Cultural Relations Between India and Southeast Asian Countries, p.87

17 Quoted in Coedes, G., The Indianised States etc., p.37

18 Ray, Himanshu Prabha, Monastery and Guild: Commerce Under theSatavahanas, p.108

CHAPTER 7

1 Williams, L.F. Rushbrook (ed.), A Handbook for Travellers in India,Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and SriLanka, p.278

2 Banerjea, J.N., ‘The Satraps of Northern and Western India’, in S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha (ed.), A Comprehensive History of India, vol.2, p.283

3 Ghoshal, U.N., ‘Political Organisation (Post-Mauryan)’, in ibid, p.350

4 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, p.285

5 Ibid, p.279

6 Ibid, p.286

7 Bagchi, P.C. and Raghavan, V., ‘Language and Literature’, in S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha (ed), A Comprehensive History of India, vol.2, pp.632-3

8 Smith, V.A., The Early History of India, p.266

9 Majumdar, R.C., ‘The Rise of the Guptas’, in HCIP, vol.3, ‘The Classical Age’, p.4

10 Fleet, J.F., Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol.3, ‘Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings and their Successors’, pp.10—17

11 Smith, V.A., The Early History of India, p.274

12 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction etc., p.313

13 Mookerji, R.K., The Gupta Empire, p.38

14 Inden, R., Imagining India, pp.239-40

15 See Williams, J.G., The Art of Gupta India, p.25

16 Beal, S., in H[i]euen Tsang, Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, vol.1, pp.xxxvii—xxxviii

17 Ibid, p.lvii

18 Altekar, A.S., ‘Religion and Philosophy’, in The Vakataka-GuptaAge (ed. Majumdar, R.C. and Altekar, A.S.), p.341

19 Devahuti, D., Harsha, A Political Study, pp.114-15

20 Quoted in Keay, J., India Discovered, pp.151-2

21 Williams, J.G., The Art of Gupta India, p.3

22 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.87

23 Basham. A.L., The Wonder that was India, p.442

24 Keith, A.B., A History of Sanskrit Literature, p.94

25 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction etc., p.284

CHAPTER 8

1 Kosambi, D.D., The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India, p.191

2 Gaur, A., Indian Charters on Copper Plates in the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Books, p.viii

3 Fleet, J.F., Corpus Inscriptionum Indicum etc., p.169

4 H[i]euen Tsang (trans. Beal, S.), Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records etc., vol.1, pp.120, 137

5 See Sudhir Ranjan Das, ‘Types of Land in North-Eastern India (from the Fourth Century to the Seventh Century)’, in Chattopadhyaya, B. (ed.) Essays in Ancient Indian Economic History, pp.62—3

6 Basham, A.L., The Wonder that was India, p.449

7 Devahuti, D., Harsha etc., p.71

8 Bana (trans. Cowell, E.R. and Thomas, F.W.), Harsa-Carita

9 H[i]euen Tsang (trans. Beal, S.), Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records etc., vol.1, p.213

10 Ibid, vol.2, p.256

11 Michell, G., Monuments of India, vol.1, p.332

12 Satianathaier, R., ‘Dynasties of South India’, in HCIP, vol.4, ‘The Classical Age’, p.262

13 Coedes, G., The Indianised States of South East Asia, p.66

14 Lamb, A., ‘Indian Influence in South East Asia’, in A Cultural History of India (ed. Basham, A.L.), p.446

15 Smithies, M., Yogyakarta, p.60

16 Dumarcay, J., The Temples of Java, p.5

17 Inden, R., Imagining India, p.230

CHAPTER 9

1 H[i]euen Tsang, Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records etc., vol.2, pp.272-3

2 Chach-nama or Tarikh-i Hind wa Sind, in HOIBIOH (ed. Elliot, H.M. and Dowson, J.), vol.1, pp.142—4

3 Al-Biladuri, in HOIBIOH, vol.1, p.119

4 Majumdar, R.C., ‘Northern India during AD 650—750’, in HCIP, vol.3 ‘The Classical Age’, p.170

5 Chach-nama etc., as above, pp.209-11

6 Al-Biladuri quoted in Ray, H.C., The Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.1, p.12

7 See Puri, B.N., The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, pp.445—6

8 Quoted in Thapar, R., A History of India, vol.1, p.239

9 See Inden, R., Imagining India, pp.217—28

10 Suleiman, in HOIBIOH, vol.1, p.7

11 Altekar, A.S., ‘The Rashtrakutas’, in The Early History of the Deccan (ed. Yazdani, G.), vol.1, p.256

12 As rendered in Inden, R., Imagining India, p.260

13 Puri, B.N., The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, p.94

14 Majumdar, R.C., ‘The Palas’, in HCIP, vol.4, ‘The Imperial Age of Kanauj’, p.53

15 Williams, L.F. Rushbrook (ed.), A Handbook for Travellers etc., p.698

16 Munshi, K.M., in HCIP, vol.4, The Imperial Age of Kanauj, p.xiv

17 Majumdar, R.C., Ancient India, p.266

18 See Altekar, A.S., ‘The Rashtrakutas’, in The Early History of the Deccan etc., vol.1, p.273

19 Inden, R., Imagining India, p.259

CHAPTER 10

1 Sulaiman, as quoted in HOIBIOH, vol.1, p.4

2 Tabaqat-i-Akbari, as quoted in Ray, H.C., The Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.1, p.81

3 Al-Utbi, Shahr-i Tarikhi Yamini, as quoted in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.20

4 Ferishta (trans. Dow, A.), The History of Hindoostan, vol.1, p.34

5 Al-Utbi, as above, p.48

6 Ibn Asir, Kamilu-t Tawarikh, quoted in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.470

7 Ferishta, The History of Hindoostan etc., vol.1, pp.33—4

8 Al-Biruni, quoted in Ganguly, D.C., ‘Ghaznavid Invasion’, in HCIP, vol.5, p.17

9 Keay, J., India Discovered, pp.98—9

10 See Punja, S., Divine Ecstasy: The Story of Khajuraho

11 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.311

12 Champakalakshmi, R., ‘State and Economy: South India c.AD 400-1300’, in Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History (ed. Thapar, R.), p.282

13 Duby, G. (trans. Clarke, H.B.), The Early Growth of the European Economy:Warriors and Peasants from the Seventh to the Twelfth Century, Ithaca, 1974, pp.51-2

14 Spencer, G.W., The Politics of Expansion: The Chola Conquest of SriLanka and Sri Vijaya, p.11

15 Karashima, N., South Indian History and Society: Studies from InscriptionsAD 850—1800, pp.37—40

16 Narayanan, M.G.S. and Kesuvan Veluthat, ‘Bhakti Movement in South India’, in Indian Movements: Some Aspects of Dissent, Protest and Reform (ed. Malik, S.), p.37

17 Champakalakshmi, R., ‘State and Economy’, as above, p.298

18 Spencer, G.W., The Politics of Expansion etc., p.39

19 S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha, The Colas

20 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., pp.321-5

21 Verma, H.C., ‘The Ghaznavid Invasions, Part 2’, in The Indian History Congress, A Comprehensive History of India, vol.4, pt 1 (ed. Sharma, R.S.), p.365

22 Sharma, R.S., Indian Feudalism, pp.195-6

23 Quoted in Ray, H.C., The Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.2, p.857

24 Keith, A.B., A History of Sanskrit Literature, p.53

25 Sharma, D., ‘The Paramaras of Malwa’, in Indian History Congress, A Comprehensive History of India’, vol.5, pp.420-2

CHAPTER 11

1 Yule, H. and Burnell, A.C., Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, p.754

2 Ferishta (trans. Briggs, J.), The History of the Rise of Mohammedan Power in India, vol.1, p.xx and e.g. p.175

3 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities of Rajas’than, vol.1, p.155

4 Ray, H.C., Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.2, p.1086

5 Elliot, H.M. and Dowson, J. (eds), HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.251

6 Nizami, K.A., Some Aspects of Religion and Politics in India during the Thirteenth Century, pp.76-7

7 Ferishta (trans. Briggs), History of the Rise etc., vol.1, p.177

8 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities etc., vol.1, p.210

9 Nizami, Khaliq Ahmed, Some Aspects etc., p.91

10 Munshi, K.M., in HCIP, vol.5, The Struggle for Empire, p.xv

11 Minhaju-s Siraj, Tabakat-i Nasiri, in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.329

12 Habib, I., in CEHI, p.67

13 Nizami, K.A., Some Aspects etc., p.90

14 Nigam, S.B.P., The Nobility Under the Sultans, p.183

15 Minhaju-s Siraj, Tabakat-i Nasiri, in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.306

16 Abu Imam, ‘Bengal in History’, in India: History and Thought (ed. Mukherjee, S.N.), pp.76-7

17 Minhaju-s Siraj etc., as above, p.332

18 Habib, I., as above, p.78

19 Ziau-u Din Barani, Tarikh-i Feroz Shahi, in HOIBIOH, vol.3, p.103

20 Ferishta (trans. Dow), The History of Hindoostan, vol.1, p.197

21 Derrett, J.D.M., The Hoysalas, p.33

22 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.155

23 Ibid, p.163

24 Venkataramanyya, N., The Early Muslim Expansion in South India, p.31

25 Ibid, p.57

26 Digby, S., in CEHI, p.97

27 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.204

28 Lal, K.S., History of the Khaljis, p.275

29 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.195

30 Ferishta (trans. Dow), The History of Hindoostan, vol.1, p.267

CHAPTER 12

1 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.235

2 Majumdar, R.C. et al, An Advanced History of India, p.317

3 Ibn Batuta (Muhammad ibn ‘Abd Allah) (trans. Gibb, H.A.R.), Travels in Africa and Asia, p.196

4 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., pp.241—2

5 Majumdar, R.C., ‘Muhammad Bin Tughluq’, in HCIP, vol.6, The Delhi Sultanate, p.64

6 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.238

7 Digby, S., in CEHI, p.97

8 Husain, A.M., The Rise and Fall of Muhammad Bin Tughluq, p.134

9 Ibn Batuta etc., Travels etc., p.204

10 Shams-i Siraj Afif, Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, in HOIBIOH, vol.3, p.312

11 Davies, P., The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, vol.2, p.138

12 Malfuzat-i Timuri (Autobiography of Timur), in HOIBIOH, vol.3, p.446

13 Ibn Batuta etc., Travels etc., p.207

14 Polo, Marco (trans. and ed. Yule, H.), The Book of Ser Marco Polo, vol.2, p.313

15 ‘The Travels of Athanasius Nikitin’, in India in the Fifteenth Century (ed. Major, R.H.), p.8

16 ‘Narrative of the Journey of Abd-er-Razzak’, in ibid, p.31

17 Ferishta (trans. Dow), The History of Hindoostan, vol.2, p.292

18 Haroon Khan Sherwani, ‘The Bahmani Kingdom’, in The Indian History Congress, A Comprehensive History of India, vol.5, pt ii, p.974

19 ‘The Travels of Athanasius Nikitin’, in India in the Fifteenth Century etc., pp.23-8

20 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.429

21 Tod, J., Annals etc., vol.1, p.231

CHAPTER 13

1 Ferishta (trans. Briggs), History of the Rise etc., vol.1, p.579

2 Lal, K.S., Twilight of the Sultanate, p.176

3 Ibid, p.180

4 Ross, D., Cambridge History of India, vol.5, p.236

5 Babur (trans. Beveridge, A.S.), Babur-nama, vol.2, p.459

6 Ibid, p.463

7 Ibid, p.477

8 Tod, J., Annals etc., vol.1, p.245

9 Babur, Babur-nama etc., vol.2, pp.628, 637

10 Ferishta (trans. Briggs), History of the Rise etc., vol.2, p.70

11 Ibid, p.79

12 Richards, J.F., ‘The Mughal Empire’, in NCHI, Pt 1, vol.5, p.11

13 Habib, I., ‘Monetary System and Prices’, in CEHI, p.360

14 Harle J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.427

15 Babur, Babur-nama etc., vol.2, p.482

16 Stein, B., Vijayanagara, in NCHI, pt 1, vol.2, p.30

17 Paes, D., in Sewell, R., A Forgotten Empire, pp.246-7

18 Majumdar, R.C. et al, An Advanced History of India, p.366

19 Stein, B., Vijayanagara etc., p.43

20 Pearson, M.N., The Portuguese in India, in NCHI, pt 1, vol.1, p.29

21 Sewell, R., A Forgotten Empire, p.207

22 Abu’l-Fazl (trans. Beveridge, H.), Akbar-nama, vol.1, pp.620-1

23 Lane-Poole, S., The History of the Moghul Emperors of Hindustan Illustrated by their Coins, Constable, London, 1892, p.lii

24 Abu’l-Fazl, Akbar-nama etc., vol.2, p.59

25 Ibid, pp.62-4

26 Ibid, vol.1, pp.27—8

27 Ibid, vol.2, pp.271—2

28 Ibid, p.236

29 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.23

30 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities etc., vol.1, p.253

CHAPTER 14

1 See especially CEHI

2 Babur, Tuzak-i Babari (Babur-nama), in HOIBIOH, vol.4, p.223

3 Habib, I., ‘North India’, in ‘Agrarian Relations and Land Revenue’, CEHI, p.238

4 Bernier, F. (trans. Constable, A.), Travels in the Mogol Empire AD 1656- 1668, pp.225—7

5 Raychaudhuri, T., ‘The Mughal Empire’, in ‘The State and the Economy’, CEHI, p.173

6 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.63

7 Raychaudhuri, T., in CEHI, p.179

8 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.86

9 Roe, Sir T. (ed. Foster, W.), The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to India,1615-19, pp.283-4

10 Bernier, F., Travels etc., p.222

11 Thevenot, J. de, ‘The Third Part of the Travels’, in Indian Travels of Thevenot and Careri (ed. Surendranath Sen), p-7

12 Jehangir, Waki’at-i Jahangiri, in HOIBIOH, vol.6, pp.292, 385

13 See Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities, vol.1, pp.278-92

14 Jehangir, Waki’at-i Jahangiri etc., p.374

15 Roe, Sir T., The Embassy etc., pp.270, 337

16 Asher, C.B., Architecture of Mughal India, in NCHI Pt 1, vol.4, p.200

17 Mundy, P., The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia, 1608-67, vol.2, p.213

18 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.127

19 Sarkar, J., History of Aurangzib, vol.1, p.302

20 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.152

21 Khafi Khan, Muntakhabu-l Lubab, in HOIBIOH, vol.7, p.246

22 Khafi Khan (ed. and trans. Moinul Haq, S.), History of Alamgir, p.159

23 See Moinul Haq, S., introduction to ibid, p.xxvii

24 Bernier, F., Travels etc., p.334

25 Khafi Khan, Muntakhabu-l etc., p.296

26 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.178

27 Gascoigne, B., The Great Moghuls, p.227

28 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities, vol.1, p.302

CHAPTER 15

1 Gordon, S., The Marathas 1600-1818, in NCHI, pt 2, vol.4, p.67

2 Khafi Khan, History of Alamgir etc., pp.122-4

3 Ibid, p.125

4 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.74

5 Sardesai, G., ‘Shivaji’, in HCIP, vol.7, The Mughal Empire, p.264

6 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.92

7 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.220

8 As quoted in Gascoigne, B., The Great Moghuls, p.238

9 Khafi Khan, Muntakhubu-l Lulab, in HOIBIOH, vol.7, p.485

10 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.256

11 Muzaffar Alam, The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India: Awadh and the Punjab, 1707—48, p.134

12 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire, in NCHI, pt 2, vol.1, p.3

13 ‘The Mahratta Manuscripts’, as quoted in Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.322

14 Khafi Khan, Muntakhubu-l Lubab, in HOIBIOH, vol.7, p.432

15 Gordon, Stewart, The Marathas etc., p.110

16 Khafi Khan, Muntakhubu-l Lubab etc., P.483

17 Ghulam Husain, Siyar-ul-Mutakherin, as quoted in Majumdar, R.C. et al, An Advanced History of India, p.529

18 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.114

19 Duff, J.C. Grant, History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.354

20 Hunter, W.W., History of India, vol.7, p.284

21 As quoted in Keay, J., The Honourable Company, pp.145—7

22 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire etc., p.48

23 Marshall, P.J., Bengal: The British Bridgehead, in NCHI, pt 2, vol.2, p.55

24 As quoted in Keay, J., The Honourable Company, p.215

25 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society etc., p.46

26 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.138

CHAPTER 16

1 See Keay, John, The Honourable Company, p.398

2 Elphinstone, Mountstuart, History of India etc., p.720

3 Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas etc., vol.1, p.511

4 Quoted in Chaudhuri, Nirad C., Clive of India, p.465

5 Marshall, P.J, East Indian Fortunes: The British in Bengal in the Eighteenth Century, pp.32-3

6 As quoted in Marshall, P.J., East Indian Fortunes etc., p.30

7 Marshall, P.J., Bengal: The British Bridgehead, pt 2, vol.2 of NCHI, p.75

8 As quoted in Keay, J., The Honourable Company, p.303

9 Marshall, P.J., Bengal: The British Bridgehead, p.77

10 Marshall, P.J., East Indian Fortunes etc., p.235

11 Moon, P., The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p.114

12 Barnett, R.B., North India Between Empires: Awadh, the Mughals and the British 1720-1801, p.64

13 Mohibbul Hasan, The History of Tipu Sultan, p.6

14 Moon P., The British Conquest etc., p.203

15 Mohibbul Hasan, The History etc., p.120

16 Ibid, p.349

17 As quoted in Majumdar, R.C. et al, Advanced History of India, p.715

18 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.261

19 Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.507

20 Ahmad Shah Abdali to Madho Singh, letter (trans. Jadunath Sarkar), in

Modern Review, May 1946, quoted in HCIP, vol.8, The Maratha Supremacy, p.199

21 Malcom, J., A Memoir of Central India, quoted in Kamath, M.B. and Kher, V.B., Devi Ahalyabhai Holkar: The Philosopher Queen, p.85

22 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.162

23 Ibid, pp.172—3

24 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.409

CHAPTER 17

1 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire etc., p.138

2 Kaye, Sir J., as quoted in Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.497

3 Mason, P., A Matter of Honour: An Account of the Indian Army, its Officers and Men, p.210

4 Sita Ram (trans. Norgate, J.T.), From Sepoy to Subedar: Being the Life and Adventures of a Native Officer in the Bengal Army, p.68

5 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., pp.567-75

6 Hugel, Baron C. von, Travels in Kashmir and the Punjab, London, 1845, p.293

7 Cunningham, A., Ladak, Physical,Statistical and Historical, London, 1854, quoted in Keay, J., When Men and Mountains Meet, John Murray, London, 1977, p.170

8 Griffin, Lepel, Ranjit Singh and the Sikh Barrier between Our Growing Empire and Central Asia, pp.9—10

9 Mason, P., A Matter of Honour etc., p.229

10 Grewal, J.S., The Sikhs of the Punjab, pt 2, vol.3 of NCHI, p.115

11 Ibid, p.127

12 Quoted in Balfour, I., Famous Diamonds, 3rd edn, London, 1997, p.168

13 Sardesai, G.S., Marathi Riyasat, Bombay, 1925, quoted in Kamath, M.V. and Kher, V.B., Ahalyabai Holkar etc., p.126

14 Nehru, Jawaharlal, The Discovery Of India, p.266

15 Malcolm, Sir J., The Political History of India, 1784-1823, London, 1826, vol.2, pp.cclxiii—iv, quoted in Cohn, B.S., Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India, pp.41-2

16 Munro, Sir T., quoted in Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.427

17 Quoted in Stokes, E., The English Utilitarians in India, p.28

18 Mill, J., The History of British India, vol.2, pp.166—7, cited in Metcalf, T.R., The Aftermath of Revolt: India 1857-70, pp.8-9

19 Trevelyan, G.O., The Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay, London, 1908 edn, pp.329-30

20 Davies, P., The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, vol.2,

Islamic,Rajput and European, p.243

21 As quoted in Pemble, J., The Raj, the Indian Mutiny and the Kingdom of Oudh 1801-1859, p.59

22 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.652

23 Metcalf, T.R., The Aftermath etc., p.46

24 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire etc., p.196

25 Sen, Surendra Nath, Eighteen Fifty-Seven, p.411

26 Ibid, p.113

27 Pemble, John, The Raj, the Indian Mutiny and the Kingdom of Oudh,1801- 59 etc., p.215

28 Lowe, T., Central India During the Rebellion of 1857 and 1858: A Narrative of Operations…, London, 1860, p. 236

29 Cohn, B.S., ‘Representing Authority in Victorian India’, in The Invention of Tradition (ed. Hobsbawn, E. and Ranger, T.), p.193

CHAPTER 18

1 Chandra, B. et al, India’s Struggle for Independence 1857—1947, p.52

2 Keay, J., Last Post: The End of Empire in the Far East, John Murray, London, 1997, p.23

3 Seal, A., The Emergence of Indian Nationalism: Competition and Collaboration in the Late Nineteenth Century, p.52

4 Sumit Sarkar, Modern India, pp.30-2

5 Bayly, C.A., Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion 1770—1870, p.450

6 Ibid, p.450

7 Cohn, B.S., ‘Representing Authority’etc., p.209

8 Seal, A., The Emergence etc., p.165

9 Quoted in ibid, p.265

10 Sayid, K.B., Pakistan: The Formative Phase 1857—1948, p.5

11 Seal, A., The Emergence etc., p.276

12 Ibid, p.278

13 Gilmour, D., Curzon, John Murray, London, 1994, p.135

14 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.912

15 Quoted in Gilmour, D., Curzon, p.271

16 Quoted in Wolpert, S., A New History of India, p.273

17 Sarkar, S., Modern India, p.134

18 Ibid, p.125

19 Mukherjee, H., India Struggles for Freedom, Bombay, 1948, p.96, quoted in Chandra, B. et al, India’s Struggle for Independence 1857-1947, p.145

20 Quoted in Moon, P., The British Conquest etc p.968

21 Sarkar, S., Modern India, p.148

22 Brown, J.M., Gandhi’s Rise to Power: Indian Politics 1915—1922, p.184

23 Robb, P.G., The Government of India and Reform: Policies Towards Politics and the Constitution 1916-21, p.179

24 Hardy, P., The Muslims of British India, p.198

25 Ibid, p.198

26 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.1012

CHAPTER 19

1 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.1039

2 Quoted in Chandra, B. et al, India’s Struggle etc., p.270

3 Brown, J.M, Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy, p.265

4 Ibid, p.277

5 Chatterji, J., Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932— 47, p.24

6 Talbot, I., ‘The Unionist Party and Punjabi Politics’, in The Political Inheritance of Pakistan (ed. Low, D.A.), pp.89—90

7 Copland, I., The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917-47, pp.166-7

8 Sarkar, S., Modern India, pp.351, 371

9 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., pp.1092-3

10 Sarkar, S., Modern India, p.406

11 The Times, London, 4 September 1947

12 Viceroy’s Personal Report No.17, 16 August 1947, quoted in Collins, L. and Lapierre, D., Chatterji, J.,Bengal Divided: Hindu Mountbatten and the Partition of India Communalism and Partition, p.177

CHAPTER 20

1 Tully, M., No Full Stops in India, p.13

2 Quoted, for example, in Jalal, A., The State of Martial Rule p.279

3 Ibid, p.159

4 Guha, R., Moon, P., India after Gandhi, p.393

5 Chandra, B. et al, India after Independence, p.96

6 Guha, R., India after Gandhi, p.333

CHAPTER 21

1 Jalal, A., The State of Martial Rule, p.98

2 Quoted in ibid, p.106

3 Ziring, L., Pakistan in the Twentieth Century, p.161

4 Ibid, p.168

5 Talbot, I., Pakistan: A Modern History, p-145

6 Ziring, L., Pakistan in the Twentieth Century p.218

7 Sen, A., The Argumentative Indian, p.188

8 Guha, R., India after Gandhi, pp.446-7

9 Bhutto, Z.A., If I am Assassinated…’, pp.142-3

10 Ziring, L., Pakistan in the Twentieth Century, p.,352

CHAPTER 22

1 Khilnani, S., The Idea of India, pp.48-9

2 Ibid, p.48

3 Bhutto, Z.A., ‘If I am Assassinated…’, p.125

4 Ziring, L., Pakistan in the 20th Century

5 Jalal, A., The State of Martial Rule, p.328

6 Bhutto, Z.A., ‘If I am Assassinated. ..’, p.234

7 Chandra, B. et al, India after Independence, p.260

8 Guha, R., India after Gandhi, p.559

9 Tully, M. and Jacob, S., Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle, pp.190-7

10 Guha, R., India after Gandhi, p.571

CHAPTER 23

1 ‘The aid workers who really matter’, The Economist, 10 October 2009

2 Cohen, S.P., The Idea of Pakistan, p.125

3 Shaikh, F., Making Sense of Pakistan, p.99

4 Duncan, Emma, ‘Pakistan: Living on the edge’, The Economist, 17 January 1987

5 Shaikh, F., Making Sense of Pakistan, p.165

6 Council on Foreign Relations report, ‘The Taliban in Afghanistan’, 03/08/09

7 Puniyani, R., ‘Liberhan Commission Report: Better Late than Never’, Tehelka, 04/12/09

8 Guha, R., India after Gandhi, p.654

9 Ibid, p.684

Publication details of most of the cited works will be found in the bibliography. The following abbreviations refer to works listed in the General section of the bibliography: CEHI – The Cambridge Economic History of India, vol.1, c1200-c1750 (ed. Raychaudhuri, T. and Habib, I.) HCIP – The History and Culture of the Indian People (ed. Majumdar, R.C. et al) HOIBIOH – The History of India as Told by its Own Historians (ed. Elliot, H.M. and Dowson, J.) NCHI – The New Cambridge History of India (ed. Johnson, G. et al)

INTRODUCTION

1 Majumdar, R.C., in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’ p.47

2 Keay, J., India Discovered, HarperCollins, London, 1988

3 Stein, B., A History of India, Blackwell, Oxford, 1998, p.5

4 Braudel, F. (trans. Maine, R.), A History of Civilisations, Penguin, New York, 1993, p.217

CHAPTER 1

1 Adapted from the Satapatha Brahmana as rendered by A.D. Pusalkar, in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’, pp.271–2

2 Thapar, R., ‘The Study of Society in Ancient India’, in Ancient Indian Social History, p.212

3 Bhandarkar, D.R., quoted in Possehl, G. (ed.), Harappan Civilisation, p.405

4 Allchin, B. and F.R., Birth of Indian Civilisation, p.131

5 Ibid, p.132

6 Ghosh, A., The City in Early Historical India, p.83

7 Lal, B.B., ‘The Indus Civilisation’, in Basham, A.L. (ed.), A Cultural History of India, p.16

8 Pusalker, A.D., in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’, p.181

9 Ratnagar, S., Enquiries into the Political Organisation of Harappan Society, p.152

10 Ratnagar, S., Encounters: The Westerly Trade of the Harappan Civilisation, p.247

CHAPTER 2

1 Thapar, R., ‘The Image of the Barbarian in Early India’, repr. in Ancient Indian Social History, p.140

2 Thapar, R., ‘The Study of Society in Ancient India’, repr. in ibid, p.190

3 Asiatick Researches, vol.1, 1788, quoted in Keay, John, India Discovered, p.30

4 Muller, F. Max, Chips from a German Workshop, vol.1, 1867, p.63

5 Wheeler, R.E. Mortimer, ‘Harappan Chronology and the Rig Veda’, repr. in Possehl, G.L. (ed.), Ancient Cities of the Indus, p.291

6 Dales, G.F., ‘The Mythical Massacre at Mohenjo Daro’, repr. in ibid, p.293

7 Elphinstone, Mountstuart, The HistoryOf India etc., p.54

8 Majumdar, R.C., Ancient India, p.30

9 Ghosh, B.K., ‘Language and Literature’, in ‘The Age of the Rik-Samhita’, bk v in HCIP, vol.1, ‘The Vedic Age’, pp.347-8

10 Rig Veda, Mandala I, 175

CHAPTER 3

1 Kosambi, D.D., The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline, p.89

2 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, p.2

3 Ibid, p.146

4 Ghosh, A., The City in Early Historical India, p.34

5 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, pp.16-17

6 Quoted in Meyer, J.T., Sexual Life in Ancient India

7 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, p.22

8 Ibid, p.134

9 Sharma, J.P., Republics in Ancient India, p.9

10 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, p.73

11 Ghosh A., The City in Early Historical India, p.64

12 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, pp.102-3

13 Rig Veda, X, 90

14 Thapar, R., From Lineage to State, p.170

15 Spelman, J.W., Political Theory of Ancient India, p.69

CHAPTER 4

1 Mountbatten, quoted in Collins, L. and Lapierre, D., Mountbatten and the Partition of India, p.70

2 Lane Fox, R., Alexander the Great, p.56

3 Marshall, J., Taxila, vol.1, p.12

4 Basham, A.L., The Wonder that was India, p.390

5 Bechert, H., in When did the Buddha Live?: The Controversy of the Dating of the Historical Buddha (ed. Bechert, H.), p.286

6 Sharma, J.P., The Republics in Ancient India, pp.123-4

7 Mookerji, R.K., in HCIP, vol.2, ‘The Age of Imperial Unity’, p.25

8 Thapar, R., A History of India, vol.1, p.59

9 Majumdar, R.C., Ancient India, p.101

10 Lane Fox, R., Alexander the Great, p.331

11 Mookerji, R.K., in HCIP, vol.2, ‘The Age of Imperial Unity’, p.44

CHAPTER 5

1 Asiatick Researches, 1793, quoted in Keay, J., India Discovered, p.35

2 Wells, H.G., A Short History of the World, 1922, repr. Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1946, p.114

3 Kautilya (ed. and trans. Rangarajan, L.N. etc.), The Arthasastra, p.21

4 Trautmann, Thomas R., Kautilya and the Arthasastra, p.186

5 Fergusson, J., A History of Indian Architecture, London, 1897

6 Yazdani, G., The Early History of the Deccan, vol.1, p.69

7 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History …, 1975, preface and pp.17–53

8 Tod, James, Travels in Western India, W.H. Allen, London, 1839, p.76

9 Prinsep, James, in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, vol.8, 1838, quoted in Keay, John, India Discovered, p.53

10 As trans. in Thapar, Romila, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, p.256

11 Mookerji, R.K., ‘Asoka the Great’, in HCIP, vol.2, ‘The Age of Imperial Unity’, p.74

12 Wells, H.G., A Short History of the World, 1922, repr. Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1946, p.115

13 Kautilya (ed. and trans. Rangarajan, L.N. etc.), The Arthasastra, p.741

14 McCrindle, J.W., Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian, Trubner, London, 1877, p.84

15 As trans. in Thapar, Romila, Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, p.254

16 Ibid, p.266

17 Thapar, R., ‘Asokan India and the Gupta Age’, in Basham, A.L. (ed.), A Cultural History of India, p.42

CHAPTER 6

1 Narain, A.K., The Indo-Greeks, p.viii

2 Kulke, H. and Rothermund, D., A History of India, p.83

3 S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha, A Comprehensive History of India, vol.2, The Mauryas and the Satavahanas, p.102

4 Thapar, Romila, A History of India, vol.1, p.93

5 Narain, A.K., The Indo-Greeks, p.11

6 Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, p.70 7 Bagchi, P.C., India and China: A Thousand Years of Cultural Relations, p.10

8 Dani, A.H., Human Records on the Karakoram Highway, p.49

9 Ibid, p.77

10 S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha, A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar, 1955, p.130

11 Hart, George L., ‘Ancient Tamil Literature: Its Scholarly Past and Future’, in Stein, Burton (ed.), Essay son South India, pp.41-2

12 Maloney, Clarence, ‘Archaeology in South India: Accomplishments and Prospects’, in ibid, p.24

13 Wheeler, R.E. Mortimer, Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontiers, p.147

14 Glover, I.C., Early Trade Relations Between India and South East Asia, pp.47-8

15 Coedes, G., The Indianised States of Southeast Asia, p.18

16 Quoted in Sarkar, H.B., Cultural Relations Between India and Southeast Asian Countries, p.87

17 Quoted in Coedes, G., The Indianised States etc., p.37

18 Ray, Himanshu Prabha, Monastery and Guild: Commerce Under theSatavahanas, p.108

CHAPTER 7

1 Williams, L.F. Rushbrook (ed.), A Handbook for Travellers in India,Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and SriLanka, p.278

2 Banerjea, J.N., ‘The Satraps of Northern and Western India’, in S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha (ed.), A Comprehensive History of India, vol.2, p.283

3 Ghoshal, U.N., ‘Political Organisation (Post-Mauryan)’, in ibid, p.350

4 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, p.285

5 Ibid, p.279

6 Ibid, p.286

7 Bagchi, P.C. and Raghavan, V., ‘Language and Literature’, in S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha (ed), A Comprehensive History of India, vol.2, pp.632-3

8 Smith, V.A., The Early History of India, p.266

9 Majumdar, R.C., ‘The Rise of the Guptas’, in HCIP, vol.3, ‘The Classical Age’, p.4

10 Fleet, J.F., Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol.3, ‘Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings and their Successors’, pp.10—17

11 Smith, V.A., The Early History of India, p.274

12 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction etc., p.313

13 Mookerji, R.K., The Gupta Empire, p.38

14 Inden, R., Imagining India, pp.239-40

15 See Williams, J.G., The Art of Gupta India, p.25

16 Beal, S., in H[i]euen Tsang, Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, vol.1, pp.xxxvii—xxxviii

17 Ibid, p.lvii

18 Altekar, A.S., ‘Religion and Philosophy’, in The Vakataka-GuptaAge (ed. Majumdar, R.C. and Altekar, A.S.), p.341

19 Devahuti, D., Harsha, A Political Study, pp.114-15

20 Quoted in Keay, J., India Discovered, pp.151-2

21 Williams, J.G., The Art of Gupta India, p.3

22 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.87

23 Basham. A.L., The Wonder that was India, p.442

24 Keith, A.B., A History of Sanskrit Literature, p.94

25 Kosambi, D.D., An Introduction etc., p.284

CHAPTER 8

1 Kosambi, D.D., The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India, p.191

2 Gaur, A., Indian Charters on Copper Plates in the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Books, p.viii

3 Fleet, J.F., Corpus Inscriptionum Indicum etc., p.169

4 H[i]euen Tsang (trans. Beal, S.), Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records etc., vol.1, pp.120, 137

5 See Sudhir Ranjan Das, ‘Types of Land in North-Eastern India (from the Fourth Century to the Seventh Century)’, in Chattopadhyaya, B. (ed.) Essays in Ancient Indian Economic History, pp.62—3

6 Basham, A.L., The Wonder that was India, p.449

7 Devahuti, D., Harsha etc., p.71

8 Bana (trans. Cowell, E.R. and Thomas, F.W.), Harsa-Carita

9 H[i]euen Tsang (trans. Beal, S.), Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records etc., vol.1, p.213

10 Ibid, vol.2, p.256

11 Michell, G., Monuments of India, vol.1, p.332

12 Satianathaier, R., ‘Dynasties of South India’, in HCIP, vol.4, ‘The Classical Age’, p.262

13 Coedes, G., The Indianised States of South East Asia, p.66

14 Lamb, A., ‘Indian Influence in South East Asia’, in A Cultural History of India (ed. Basham, A.L.), p.446

15 Smithies, M., Yogyakarta, p.60

16 Dumarcay, J., The Temples of Java, p.5

17 Inden, R., Imagining India, p.230

CHAPTER 9

1 H[i]euen Tsang, Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records etc., vol.2, pp.272-3

2 Chach-nama or Tarikh-i Hind wa Sind, in HOIBIOH (ed. Elliot, H.M. and Dowson, J.), vol.1, pp.142—4

3 Al-Biladuri, in HOIBIOH, vol.1, p.119

4 Majumdar, R.C., ‘Northern India during AD 650—750’, in HCIP, vol.3 ‘The Classical Age’, p.170

5 Chach-nama etc., as above, pp.209-11

6 Al-Biladuri quoted in Ray, H.C., The Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.1, p.12

7 See Puri, B.N., The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, pp.445—6

8 Quoted in Thapar, R., A History of India, vol.1, p.239

9 See Inden, R., Imagining India, pp.217—28

10 Suleiman, in HOIBIOH, vol.1, p.7

11 Altekar, A.S., ‘The Rashtrakutas’, in The Early History of the Deccan (ed. Yazdani, G.), vol.1, p.256

12 As rendered in Inden, R., Imagining India, p.260

13 Puri, B.N., The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, p.94

14 Majumdar, R.C., ‘The Palas’, in HCIP, vol.4, ‘The Imperial Age of Kanauj’, p.53

15 Williams, L.F. Rushbrook (ed.), A Handbook for Travellers etc., p.698

16 Munshi, K.M., in HCIP, vol.4, The Imperial Age of Kanauj, p.xiv

17 Majumdar, R.C., Ancient India, p.266

18 See Altekar, A.S., ‘The Rashtrakutas’, in The Early History of the Deccan etc., vol.1, p.273

19 Inden, R., Imagining India, p.259

CHAPTER 10

1 Sulaiman, as quoted in HOIBIOH, vol.1, p.4

2 Tabaqat-i-Akbari, as quoted in Ray, H.C., The Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.1, p.81

3 Al-Utbi, Shahr-i Tarikhi Yamini, as quoted in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.20

4 Ferishta (trans. Dow, A.), The History of Hindoostan, vol.1, p.34

5 Al-Utbi, as above, p.48

6 Ibn Asir, Kamilu-t Tawarikh, quoted in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.470

7 Ferishta, The History of Hindoostan etc., vol.1, pp.33—4

8 Al-Biruni, quoted in Ganguly, D.C., ‘Ghaznavid Invasion’, in HCIP, vol.5, p.17

9 Keay, J., India Discovered, pp.98—9

10 See Punja, S., Divine Ecstasy: The Story of Khajuraho

11 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.311

12 Champakalakshmi, R., ‘State and Economy: South India c.AD 400-1300’, in Recent Perspectives of Early Indian History (ed. Thapar, R.), p.282

13 Duby, G. (trans. Clarke, H.B.), The Early Growth of the European Economy:Warriors and Peasants from the Seventh to the Twelfth Century, Ithaca, 1974, pp.51-2

14 Spencer, G.W., The Politics of Expansion: The Chola Conquest of SriLanka and Sri Vijaya, p.11

15 Karashima, N., South Indian History and Society: Studies from InscriptionsAD 850—1800, pp.37—40

16 Narayanan, M.G.S. and Kesuvan Veluthat, ‘Bhakti Movement in South India’, in Indian Movements: Some Aspects of Dissent, Protest and Reform (ed. Malik, S.), p.37

17 Champakalakshmi, R., ‘State and Economy’, as above, p.298

18 Spencer, G.W., The Politics of Expansion etc., p.39

19 S[h]astri, K.A. Nilakantha, The Colas

20 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., pp.321-5

21 Verma, H.C., ‘The Ghaznavid Invasions, Part 2’, in The Indian History Congress, A Comprehensive History of India, vol.4, pt 1 (ed. Sharma, R.S.), p.365

22 Sharma, R.S., Indian Feudalism, pp.195-6

23 Quoted in Ray, H.C., The Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.2, p.857

24 Keith, A.B., A History of Sanskrit Literature, p.53

25 Sharma, D., ‘The Paramaras of Malwa’, in Indian History Congress, A Comprehensive History of India’, vol.5, pp.420-2

CHAPTER 11

1 Yule, H. and Burnell, A.C., Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, p.754

2 Ferishta (trans. Briggs, J.), The History of the Rise of Mohammedan Power in India, vol.1, p.xx and e.g. p.175

3 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities of Rajas’than, vol.1, p.155

4 Ray, H.C., Dynastic History of Northern India, vol.2, p.1086

5 Elliot, H.M. and Dowson, J. (eds), HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.251

6 Nizami, K.A., Some Aspects of Religion and Politics in India during the Thirteenth Century, pp.76-7

7 Ferishta (trans. Briggs), History of the Rise etc., vol.1, p.177

8 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities etc., vol.1, p.210

9 Nizami, Khaliq Ahmed, Some Aspects etc., p.91

10 Munshi, K.M., in HCIP, vol.5, The Struggle for Empire, p.xv

11 Minhaju-s Siraj, Tabakat-i Nasiri, in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.329

12 Habib, I., in CEHI, p.67

13 Nizami, K.A., Some Aspects etc., p.90

14 Nigam, S.B.P., The Nobility Under the Sultans, p.183

15 Minhaju-s Siraj, Tabakat-i Nasiri, in HOIBIOH, vol.2, p.306

16 Abu Imam, ‘Bengal in History’, in India: History and Thought (ed. Mukherjee, S.N.), pp.76-7

17 Minhaju-s Siraj etc., as above, p.332

18 Habib, I., as above, p.78

19 Ziau-u Din Barani, Tarikh-i Feroz Shahi, in HOIBIOH, vol.3, p.103

20 Ferishta (trans. Dow), The History of Hindoostan, vol.1, p.197

21 Derrett, J.D.M., The Hoysalas, p.33

22 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.155

23 Ibid, p.163

24 Venkataramanyya, N., The Early Muslim Expansion in South India, p.31

25 Ibid, p.57

26 Digby, S., in CEHI, p.97

27 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.204

28 Lal, K.S., History of the Khaljis, p.275

29 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.195

30 Ferishta (trans. Dow), The History of Hindoostan, vol.1, p.267

CHAPTER 12

1 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.235

2 Majumdar, R.C. et al, An Advanced History of India, p.317

3 Ibn Batuta (Muhammad ibn ‘Abd Allah) (trans. Gibb, H.A.R.), Travels in Africa and Asia, p.196

4 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., pp.241—2

5 Majumdar, R.C., ‘Muhammad Bin Tughluq’, in HCIP, vol.6, The Delhi Sultanate, p.64

6 Ziau-d Din Barani, Tarikh-i-Feroz Shahi etc., p.238

7 Digby, S., in CEHI, p.97

8 Husain, A.M., The Rise and Fall of Muhammad Bin Tughluq, p.134

9 Ibn Batuta etc., Travels etc., p.204

10 Shams-i Siraj Afif, Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, in HOIBIOH, vol.3, p.312

11 Davies, P., The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, vol.2, p.138

12 Malfuzat-i Timuri (Autobiography of Timur), in HOIBIOH, vol.3, p.446

13 Ibn Batuta etc., Travels etc., p.207

14 Polo, Marco (trans. and ed. Yule, H.), The Book of Ser Marco Polo, vol.2, p.313

15 ‘The Travels of Athanasius Nikitin’, in India in the Fifteenth Century (ed. Major, R.H.), p.8

16 ‘Narrative of the Journey of Abd-er-Razzak’, in ibid, p.31

17 Ferishta (trans. Dow), The History of Hindoostan, vol.2, p.292

18 Haroon Khan Sherwani, ‘The Bahmani Kingdom’, in The Indian History Congress, A Comprehensive History of India, vol.5, pt ii, p.974

19 ‘The Travels of Athanasius Nikitin’, in India in the Fifteenth Century etc., pp.23-8

20 Harle, J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.429

21 Tod, J., Annals etc., vol.1, p.231

CHAPTER 13

1 Ferishta (trans. Briggs), History of the Rise etc., vol.1, p.579

2 Lal, K.S., Twilight of the Sultanate, p.176

3 Ibid, p.180

4 Ross, D., Cambridge History of India, vol.5, p.236

5 Babur (trans. Beveridge, A.S.), Babur-nama, vol.2, p.459

6 Ibid, p.463

7 Ibid, p.477

8 Tod, J., Annals etc., vol.1, p.245

9 Babur, Babur-nama etc., vol.2, pp.628, 637

10 Ferishta (trans. Briggs), History of the Rise etc., vol.2, p.70

11 Ibid, p.79

12 Richards, J.F., ‘The Mughal Empire’, in NCHI, Pt 1, vol.5, p.11

13 Habib, I., ‘Monetary System and Prices’, in CEHI, p.360

14 Harle J.C., Art and Architecture etc., p.427

15 Babur, Babur-nama etc., vol.2, p.482

16 Stein, B., Vijayanagara, in NCHI, pt 1, vol.2, p.30

17 Paes, D., in Sewell, R., A Forgotten Empire, pp.246-7

18 Majumdar, R.C. et al, An Advanced History of India, p.366

19 Stein, B., Vijayanagara etc., p.43

20 Pearson, M.N., The Portuguese in India, in NCHI, pt 1, vol.1, p.29

21 Sewell, R., A Forgotten Empire, p.207

22 Abu’l-Fazl (trans. Beveridge, H.), Akbar-nama, vol.1, pp.620-1

23 Lane-Poole, S., The History of the Moghul Emperors of Hindustan Illustrated by their Coins, Constable, London, 1892, p.lii

24 Abu’l-Fazl, Akbar-nama etc., vol.2, p.59

25 Ibid, pp.62-4

26 Ibid, vol.1, pp.27—8

27 Ibid, vol.2, pp.271—2

28 Ibid, p.236

29 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.23

30 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities etc., vol.1, p.253

CHAPTER 14

1 See especially CEHI

2 Babur, Tuzak-i Babari (Babur-nama), in HOIBIOH, vol.4, p.223

3 Habib, I., ‘North India’, in ‘Agrarian Relations and Land Revenue’, CEHI, p.238

4 Bernier, F. (trans. Constable, A.), Travels in the Mogol Empire AD 1656- 1668, pp.225—7

5 Raychaudhuri, T., ‘The Mughal Empire’, in ‘The State and the Economy’, CEHI, p.173

6 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.63

7 Raychaudhuri, T., in CEHI, p.179

8 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.86

9 Roe, Sir T. (ed. Foster, W.), The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to India,1615-19, pp.283-4

10 Bernier, F., Travels etc., p.222

11 Thevenot, J. de, ‘The Third Part of the Travels’, in Indian Travels of Thevenot and Careri (ed. Surendranath Sen), p-7

12 Jehangir, Waki’at-i Jahangiri, in HOIBIOH, vol.6, pp.292, 385

13 See Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities, vol.1, pp.278-92

14 Jehangir, Waki’at-i Jahangiri etc., p.374

15 Roe, Sir T., The Embassy etc., pp.270, 337

16 Asher, C.B., Architecture of Mughal India, in NCHI Pt 1, vol.4, p.200

17 Mundy, P., The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia, 1608-67, vol.2, p.213

18 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.127

19 Sarkar, J., History of Aurangzib, vol.1, p.302

20 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.152

21 Khafi Khan, Muntakhabu-l Lubab, in HOIBIOH, vol.7, p.246

22 Khafi Khan (ed. and trans. Moinul Haq, S.), History of Alamgir, p.159

23 See Moinul Haq, S., introduction to ibid, p.xxvii

24 Bernier, F., Travels etc., p.334

25 Khafi Khan, Muntakhabu-l etc., p.296

26 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.178

27 Gascoigne, B., The Great Moghuls, p.227

28 Tod, J., Annals and Antiquities, vol.1, p.302

CHAPTER 15

1 Gordon, S., The Marathas 1600-1818, in NCHI, pt 2, vol.4, p.67

2 Khafi Khan, History of Alamgir etc., pp.122-4

3 Ibid, p.125

4 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.74

5 Sardesai, G., ‘Shivaji’, in HCIP, vol.7, The Mughal Empire, p.264

6 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.92

7 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.220

8 As quoted in Gascoigne, B., The Great Moghuls, p.238

9 Khafi Khan, Muntakhubu-l Lulab, in HOIBIOH, vol.7, p.485

10 Richards, J.F., The Mughal Empire etc., p.256

11 Muzaffar Alam, The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India: Awadh and the Punjab, 1707—48, p.134

12 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire, in NCHI, pt 2, vol.1, p.3

13 ‘The Mahratta Manuscripts’, as quoted in Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.322

14 Khafi Khan, Muntakhubu-l Lubab, in HOIBIOH, vol.7, p.432

15 Gordon, Stewart, The Marathas etc., p.110

16 Khafi Khan, Muntakhubu-l Lubab etc., P.483

17 Ghulam Husain, Siyar-ul-Mutakherin, as quoted in Majumdar, R.C. et al, An Advanced History of India, p.529

18 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.114

19 Duff, J.C. Grant, History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.354

20 Hunter, W.W., History of India, vol.7, p.284

21 As quoted in Keay, J., The Honourable Company, pp.145—7

22 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire etc., p.48

23 Marshall, P.J., Bengal: The British Bridgehead, in NCHI, pt 2, vol.2, p.55

24 As quoted in Keay, J., The Honourable Company, p.215

25 Bayly, C.A., Indian Society etc., p.46

26 Gordon, S., The Marathas etc., p.138

CHAPTER 16

1 See Keay, John, The Honourable Company, p.398

2 Elphinstone, Mountstuart, History of India etc., p.720

3 Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas etc., vol.1, p.511

4 Quoted in Chaudhuri, Nirad C., Clive of India, p.465

5 Marshall, P.J, East Indian Fortunes: The British in Bengal in the Eighteenth Century, pp.32-3

6 As quoted in Marshall, P.J., East Indian Fortunes etc., p.30

7 Marshall, P.J., Bengal: The British Bridgehead, pt 2, vol.2 of NCHI, p.75

8 As quoted in Keay, J., The Honourable Company, p.303

9 Marshall, P.J., Bengal: The British Bridgehead, p.77

10 Marshall, P.J., East Indian Fortunes etc., p.235

11 Moon, P., The British Conquest and Dominion of India, p.114

12 Barnett, R.B., North India Between Empires: Awadh, the Mughals and the British 1720-1801, p.64

13 Mohibbul Hasan, The History of Tipu Sultan, p.6

14 Moon P., The British Conquest etc., p.203

15 Mohibbul Hasan, The History etc., p.120

16 Ibid, p.349

17 As quoted in Majumdar, R.C. et al, Advanced History of India, p.715

18 Moon, P., The British Conquest etc., p.261

19 Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.507

20 Ahmad Shah Abdali to Madho Singh, letter (trans. Jadunath Sarkar), in