THE SECRETS OF LARRY KING AND CRAIG SPENCE

Bruce Ritter was not the only man accused of preying on minors that would have contacts nestled deep within the national power structure and with institutions involved in Contra financing. Around the same time as Ritter’s downfall, a sordid child sex trafficking and abuse network began to be exposed. Centered in Omaha, Nebraska, it is remembered today as the “Franklin Scandal.” The man at the center of this scandal was Lawrence “Larry” King, a prominent local Republican activist and lobbyist who ran the Franklin Community Federal Credit Union until it was shut down by federal authorities in November 1988.

According to journalist and author Nick Bryant, the earliest mention of King in the press was 1973, when the Omaha Sun reported that King had served in the Air Force from 1965 to 1969, where he worked as an “information specialist” and handled “top secret” military communications. After an honorable discharge from the Air Force, he began studying for a career in the banking industry. At age 25, he joined a “management training program” at First National Bank in Omaha. Unsatisfied, he quit the bank in August 1970 and, later that year, Larry’s father was offered the reins of the faltering Franklin Community Credit Union. His father declined, but suggested the Credit Union hire his son as its manager. The 1973 Omaha Sun article, as cited by Bryant, lauded King for his supposed industriousness and work ethos at Franklin.81

Eventually, and many years before the Credit Union collapsed, King began to use its funds as “his personal, bottomless ATM.” His personal wealth greatly increased and King soon began making major political connections, mainly in the Republican Party, which King had joined in 1981.82

King soon founded and later chaired the Nebraska Frederick Douglas Republican Council, which threw a reception honoring King in 1983 for his “service to the Republican party both locally and nationally.” He became involved in the National Black Republican Council, where he held several positions, as well as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, where he served as “Secretary/Treasurer.” Author Nick Bryant has noted that King seemed “particularly interested in children” as he also became involved with the child-oriented organizations Camp Fire Girls, the Girls Club, and Head Start during this period.83

By the late 1980s, King was hosting parties attended by major political figures, such as Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as well as Congressmen Jack Kemp (a friend of Cohn’s) and Hal Daub. Daub, who represented Nebraska, “had a stint on Franklin’s Advisory Board,” according to Nick Bryant.84 King also donated to Daub and held a fundraiser for him while also generously donating to Republican Kay Orr’s campaign for Nebraska governor. In 1982, King sang the Star Spangled Banner at a National Black Republican Council dinner attended by Ronald and Nancy Reagan and he would go on to sing the national anthem at the 1984 Republican convention in Dallas. King’s political connections continued to grow, leading him to form the Council of Minority Americans. A gala hosted by the Council included former President Gerald Ford, Jack Kemp, and Alexander Haig (mentioned throughout Chapter 5) on its “host committee.”85

These deep connections to the Republican power base in the 1980s also led King to apparently become involved in the financing of Nicaragua’s Contras. Hints of King’s ties to Contra financing networks first emerged in a May 1989 article in the Omaha World Herald, which states that: “In the 6-1/2 months since federal authorities closed Franklin, rumors have persisted that money from the credit union somehow found its way to the Nicaraguan contra rebels.”86 The possibility that King’s fraudulent credit union was covertly funding the Contras was supported by subsequent reporting by the Houston Post’s Pete Brewton, who discovered that the CIA, in conjunction with organized crime, had secretly borrowed money from various savings and loans (S&L) institutions to fund covert operations.87 One of those S&Ls, Silverado, had Neil Bush, George H.W. Bush’s son, on its board and it had done business with King’s organization.

Another link between King and the Iran-Contra affair is King’s donation of over $25,350 to an organization affiliated with the Reagan administration, Citizens for America, which sponsored speaking trips for Oliver North and Contra leaders.88 The group was said to have been “one of the conservative Washington-based groups that advised former Lt. Col. Oliver L. North and helped develop a base of citizen support for him.” 89 Other groups in this orbit included the aforementioned AmeriCares. The then-chairman of the group, Donald Devine, stated that they “supported the Reagan administration’s effort to supply the Contras with US military aid,” but did not directly “funnel money to the rebels.”90

An officer at Citizens for America at the time was David Carmen, who – after leaving the group – ran a public relations firm called Carmen, Carmen & Hugel with his father Gerald, who had also been appointed by Reagan to head the General Services Administration and then appointed to a subsequent ambassadorship, and the former head of covert operations at the Casey-led CIA, Max Hugel.91

A 1989 article from the Omaha World Herald stated that King’s donation of $25,350 netted him access to Citizens for America’s “founders club.”92 Other members of the group’s founders club included Ivan Boesky, the insider trader tied to Drexel Burnham Lambert, and the corporate raider T. Boone Pickens. Boesky boasted longstanding ties to Max Fisher, a mentor of Leslie Wexner’s.93 Pickens was a major shareholder in Occidental Petroleum, which was run by Armand Hammer and somewhat involved in BCCI’s entry into the US financial system (See Chapter 7).94

King made the $25,350 donation in 1987 and also made other “gifts” to the organization. A lawsuit filed against King by the National Credit Union Administration alleged that the large donation had been made with money he had looted from the Franklin Credit Union.95 King’s donations to Citizens for America made up roughly half of the approximate $55,000 King spent on political donations in total before Franklin’s collapse.96

King’s criminal activities extended far beyond the looting of the Credit Union he managed, although it would be the investigation into the Credit Union that would help expose his other acts. In reality, King was a key “pimp” in an “interstate pedophile network” that trafficked mostly vulnerable children, particularly orphans from Boys Town Nebraska, across the United States.97

Hints of this emerged in the New York Times in 1988, which cited Nebraska State Senator Ernie Chambers as having been “told of boys and girls, some of them from foster homes, who had been transported around the country by airplane to provide sexual favors, for which they were rewarded,” as part of King’s activities.98 The New York Times also cited various law enforcement sources as stating that money-laundering and drugs were also part of the investigations. King’s pedophile ring in Omaha allegedly involved many of the city’s most powerful men, including Harold Andersen, publisher of the Omaha World Herald and friend of fellow Nebraskan Robert Keith Gray, as well as Omaha Police Chief Robert Wadman.99 Then-Attorney General of Nebraska Robert Spire was also a “friend” of King’s who attended King-hosted parties. Spire was later accused of “sitting on” allegations related to King’s criminal activities.100

Several of the witnesses critical to the story of the Franklin Scandal – Alisha Owen, Paul Bonacci, Danny King, and Troy Boner – independently told investigators that there were abused in other ways, not just sexually, by Larry King’s network. Per their accounts, they were also victims of sadistic physical abuse, which included suffering from whippings, knife wounds, and cigarette burns.101 Some of the witnesses revealed that they had seen other children at King’s “parties” and “orgies” who had claimed to have been kidnapped from their homes, some as young as twelve. At least one told of a child whose molestation, torture, and subsequent murder were all filmed by King and a group of adults.102

While King was mainly based in Omaha, he was also active in Washington DC, where he maintained a $5,000 per month residence off of Embassy Row.103 Intimately related to King’s DC activities was a man named Craig Spence. Spence had gotten his start as a press assistant for the Governor of Massachusetts before joining ABC News as a Vietnam War correspondent. According to some of his fellow Vietnam correspondents, Spence appeared to have an “inside track on seemingly clandestine information.” He later moved to Tokyo, where he forged a business relationship with a Japanese politician named Motoo Shiina.

Shiina, after and during his relationship with Spence, was accused of “passing US military secrets to the Soviets.” Notably, Shiina appears to have been a member of the Trilateral Commission, the body founded by David Rockefeller and Zbigniew Brzezinski, which has been accused of pursuing policies that involve the transfer of US technology to China and Russia under the guise of “normalizing” relations and building a “new international economic order.”104 In 1991, Shiina co-authored a book published by the Trilateral Commission entitled Global Competition After the Cold War: A Reassessment of Trilateralism with Kurt Biedenkopf and Joseph S. Nye Jr.105 Nye later went on to head the North American branch of the Trilateral Commission.

In the 1980s, after Shiina was accused of passing “military secrets” to the Russians, it was subsequently suggested by a member of Congress that Spence himself may have been involved in this alleged transfer of sensitive technology to China and Russia. Shortly thereafter, Shiina and Spence parted ways bitterly in 1983. Spence later stated that two bank transfers Shiina had sent him had come “into the country illegally from Hong Kong.”106 Spence had used the money to purchase a lavish property in the DC area, which would become central to his story.

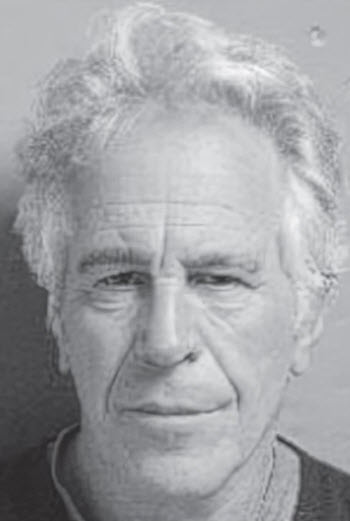

Once established in DC, Spence became a prominent lobbyist. In the early 1980s, before he parted ways with Motoo Shiina, he described himself as an “international business consultant, party host, registered foreign agent” and a “research journalist.”107 His clients included “a number of American multinational companies.” Much like Jeffrey Epstein, Spence was often compared to Jay Gatsby, the mysterious, wealthy figure from the well-known Fitzgerald novel The Great Gatsby. A 1982 New York Times article written about Spence said “what most impresses, if not benefits, his clients is his ability to master the social and political chemistry of this city, to make and use important connections and to bring together policy makers, power brokers, and opinion shapers at parties and seminars.” It then stated that “there seems to be an inexhaustible demand in Washington for the sort of thing Mr. Spence offers.”108

The Times also noted that Spence’s “personal phone book and party guest lists constitute a ‘Who’s Who’ in Congress, Government, and journalism” and that Spence was “hired by his clients as much for whom he knows as what he knows.” Spence also had a reputation for throwing lavish parties, which the Times described as “glitter[ed] with notables, from ambassadors to television stars, from senators to senior State Department officials.”109 “According to Mr. Spence,” the Times article continues, “Richard Nixon is a friend. So is [former Attorney General under Nixon] John Mitchell. [CBS journalist] Eric Sevareid is termed ‘an old, dear friend.’ Senator John Glenn is ‘a good friend’ and Peter Ustinov [British actor and journalist] is ‘an old, old friend.’”110 Notably, Jeffrey Epstein claimed to be friends with John Mitchell while Ustinov wrote for The European newspaper soon after it was founded in 1990 by Robert Maxwell, and where Ghislaine Maxwell also held a position.111 Glenn, who represented Ohio, later flew on Jeffrey Epstein’s jet to attend a birthday dinner for one of Ohio’s richest political donors, Leslie Wexner.112 Roy Cohn, William Casey, and Roy Cohn’s journalist friend William Safire were just some of the other attendees at Spence’s festivities. Cohn, it turns out, was another “good friend” of Spence’s and Spence had hosted at least one birthday party for Roy Cohn at his DC area home.

It was revealed just seven years after the New York Times published its doting profile of Spence that his “glittery parties for key officials of the Reagan and Bush administrations, media stars, and top military officers” had been bugged in order “to compromise guests.” According to the explosive report published by the Washington Times, Spence was linked to a “homosexual prostitution ring” whose clients included “government officials, locally based U.S. military officers, businessmen, lawyers, bankers, congressional aides, media representatives, and other professionals.”113 Spence also offered cocaine to his guests as another means of acquiring blackmail.

According to the report, Spence’s home “was bugged and had a secret two-way mirror, and … he attempted to ensnare visitors into compromising sexual encounters that he could then use as leverage.” One man who spoke to the Washington Times said that Spence sent a limousine to his home, which took him to a party where “several young men tried to become friendly with him.” According to John DeCamp, Spence was known to offer his guests young children for sex at his blackmail parties.114

Several other sources cited by the Washington Times, including a Reagan White House official and an Air Force sergeant who had attended Spence-hosted parties, confirmed that Spence’s house was filled with recording equipment, which he regularly used to spy on and record guests, and his house also included a two-way mirror that he used for eavesdropping.115

The report also documented Spence’s alleged connections to US intelligence, particularly the CIA. According to the Washington Times report, Spence “often boasted that he was working for the CIA and on one occasion said he was going to disappear for awhile ‘because he had an important CIA assignment.’” He was also quite paranoid about his alleged work for the agency, as he expressed concern “that the CIA might ‘double-cross him’ and kill him instead and then make it look like a suicide.”116 Not long after the Washington Times report on his activities was published, Spence fell from grace and was later found dead in the Boston Ritz Carlton. His death was ruled a suicide.

The Washington Times report also offers a clue as to what Spence may have done for the CIA, as it cited sources that said Spence had spoken of smuggling cocaine into the US from El Salvador, an operation that he claimed involved US military personnel.117 Given the timing of these comments from Spence, Spence’s powerful connections, and the CIA’s involvement in the exchange of cocaine for weapons in the Iran-Contra scandal, his comments could have been more than just boasts intended to impress his party guests.

One of the most critical parts of the scandal surrounding Spence, however, was the fact that he had been able to enter the White House late at night during the George H.W. Bush administration with young men whom the Washington Times described as “call boys.”118 After his fall from grace, Spence later stated that his contacts within the White House, which allowed him and his “call boys” afterhours access, were “top level” officials and he specifically singled out George H.W. Bush’s then-National Security Advisor Donald Gregg.119 Gregg had worked at the CIA since 1951 before he resigned in 1982 to become National Security Advisor to Bush, who was then vice president. Gregg denied Spence’s allegations.

Prior to resigning from his post at the CIA, Gregg had worked directly under William Casey and, in the late 1970s, had worked alongside a young William Barr in stonewalling the Pike Committee and the Church Committee, which investigated the CIA beginning in 1975.120 Among the things that these committees were tasked with investigating were the CIA’s “love traps,” or sexual blackmail operations used to lure foreign diplomats to bugged apartments, complete with recording equipment and two-way mirrors.121 Gregg’s role in Iran-Contra and other events during the Reagan years are discussed in Chapter 7.

The Washington Times article on this affair, stated that there was an official inquiry into Spence’s activities and blackmail. However, it appeared to imply that the Department of Justice official managing the inquiry had a conflict of interest. It states:

The office of US Attorney General Jay B. Stephens, former deputy White House counsel to President Reagan, is coordinating federal aspects of the inquiry but refused to discuss the investigation or grand jury actions.

Several former White House colleagues of Mr. Stephens are listed among clients of the homosexual prostitution ring, according to the credit card records, and those persons have confirmed that the charges were theirs.

Mr. Stephens’ office, after first saying it would cooperate with The Times’ inquiry, withdrew the offer late yesterday and also declined to say whether Mr. Stephens would recuse himself from the case because of possible conflict of interest.

At least one highly placed Bush administration official and a wealthy businessman who procured homosexual prostitutes from the escort services operated by the ring are cooperating with the investigation, several sources said.

Among clients who charged homosexual prostitutes services on major credit cards over the past 18 months are Charles K. Dutcher, former associate director of presidential personnel in the Reagan administration, and Paul R. Balach, Labor Secretary Elizabeth Dole’s political personnel liaison to the White House.”122

Despite the names that surfaced in connection with Spence, including several different White House connections, it seems that – following his fall from grace and death – interest in the case disappeared and was largely memory-holed, not unlike what would follow years later in the Jeffrey Epstein case.

The information contained within the Washington Times reports was subsequently corroborated by Henry Vinson, who operated the “largest gay escort service ever uncovered in DC.” Vinson had been significantly involved with Spence in Washington, DC and had received “thousands and thousands of dollars a month” from Spence at his escort service. Vinson claimed that he had been invited by Spence to his home “on numerous occasions” and that Vinson witnessed Spence flaunt his predilection for “cocaine and little boys.” “He [Spence] was definitely a pedophile,” Vinson would later tell Nick Bryant.123

Spence had also showcased his blackmail equipment to Vinson. Vinson, as quoted in Bryant’s Franklin Scandal, stated:

Spence showed me the hidden, secret recording devices that were scattered throughout his home.… Spence often alluded to the fact that he was connected to the CIA, and it was obvious to me that he was very well connected. There were people at his home who said they were CIA, and at least one or two Secret Service agents – I believe that it was some of the CIA operatives who installed Spence’s blackmail equipment. Much of Spence’s influence came from the House of Representatives and the Senate, and he told me he was blackmailing Congressmen. I believe that Spence was blackmailing both for the CIA and for his own personal purposes.124

Vinson alleged that former CIA director William Casey was also a “personal friend” of Spence and attended his parties. Vinson additionally alleged that Casey had been one of his patrons, in addition to Spence, and had begun requesting gay escorts from Vinson in 1986. Vinson stated that Casey’s “preferred escort was an eighteen-year-old with minimal body hair and a slender swimmer’s physique.” Vinson asserted that Casey had requested underage escorts, which Vinson declined to provide.125 It would be Vinson’s refusal to supply underage escorts to Craig Spence that would bring about his downfall and subsequent arrest.126

Vinson also told Nick Bryant that Spence and Larry King were “partners” and “hooked up with the CIA,” stating specifically that “King and Spence were in business together, and their business was pedophilic blackmail.” “They were transporting children all over the country. They would arrange for children to be flown into Washington, DC and also arrange for influential people in DC to be flown out to the Midwest and meet these kids.”

Paul Rodriguez, one of the Washington Times journalists who had helped expose Spence, also later told Nick Bryant that Spence and King had been partners, stating “I was told by several prostitutes along with law enforcement that there were connections between Craig Spence and Larry King. The allegations were that Spence and King hosted parties and were involved in a variety of nefarious activities: the allegations included Spence and King hosting blackmail sex parties that included minors and illegal drug use.” Bryant also corroborated the Spence-King connection with Rusty Nelson and Paul Bonacci, who had both met Spence through King on different occasions.127

Per Vinson, Larry King had confided in him that he had clients who liked to torture and even kill children: “King said they had clients who actually liked having sex with kids as they tortured or killed the kid. I found that totally unbelievable.” After Vinson said this to Nick Bryant, he asked Bryant later on in the interview if King’s disclosure had indeed been true.128 He was unaware at the time that other evidence, including witness testimony, had suggested that it was.

FROM OMAHA TO COLUMBUS: EXECUTIVE JET AVIATION

Larry King, before the Franklin Credit Union and related scandals completely unraveled, made extensive use of an airline called Executive Jet Aviation (EJA). King appears in the July 1987 issue of Jet magazine, where he was being congratulated personally by EJA executives Joseph B. Campbell and Skip Hockman “for being the passenger aboard the EJA jet that flew the company’s 1 millionth mile of service” and was even “presented a model of the aircraft” on which he had flown. Jet also described King as being “a frequent user of EJA’s service.”129 When EJA was later roped into a Congressional inquiry, accusations of the airline’s alleged involvement in procuring girls for clients made their way into the questioning of company executives, as did allegations of the girls’ exploitation for the purposes of blackmail.130

EJA was founded as Executive Jet Airways in 1964 by Brig. Gen. Olbert “Dick” Fearing Lassiter, an Air Force officer who was “known for his lust for excitement and fast living,” characteristics which earned him the nickname “Rapid Richard.”131 EJA was originally founded in Delaware, but Lassiter quickly moved the company to Columbus, Ohio. Lassiter had been stationed in Columbus at Lockbourne Air Force Base, now known as Rickenbacker Airport, and was still a part of the Air Force when he incorporated EJA. Lassiter allegedly relocated EJA to Columbus mainly because “of the friendships he had made there.”132

EJA’s initial board of directors included actor Jimmy Stewart, former Assistant Secretary of the Navy James H. Smith, and former chairman of the Rockefeller family’s Standard Oil branch in New Jersey, Monroe J. Rathbone.133 At the time of its founding, it was “a closely held secret” that EJA had been financed by the American Contract Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

In 1965, the company adopted the name Executive Jet Aviation and created a subsidiary based in Switzerland. The Swiss subsidiary was largely led by Paul Tibbets, who served as its executive vice president and general manager.134 Tibbets, who had also been on the founding board of EJA, is best known as the pilot of the Enola Gay when it dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima at the close of World War II. By 1967, Tibbets and others left EJA. Tibbets allegedly left because “he believed some things that were going on [at the airline] were flagrantly illegal.”

That same year, the parent company of the American Contract Company, the Pennsylvania Railroad, merged with the New York Central Railroad to form the Penn Central Transportation Company, better known as Penn Central. Rockefeller interests and Clinton Murchison Sr. were among those with financial stakes in New York Central and its subsidiaries at the time. The railroad also did significant business, including mergers and acquisitions, with individuals closely tied to the CIA-linked David Baird Foundation (see Chapters 1 and 4).135 Penn Central would collapse in 1971, becoming one of the biggest bankruptcies in US history and what Peter Dale Scott referred to as “bankruptcy fraud with organized crime overtones.”136

It would later emerge that Bruce Sundlun, a Washington attorney with past ties to Lassiter who was also on the EJA board of directors, would be responsible for the “covert” marriage between Pennsylvania Railroad/Penn Central and EJA. Their joining was performed by Glore Forgan at Sundlun’s behest. Glore Forgan’s vice president was General Charles Hodge, a Wall Street broker who was also the chief investment advisor to Penn Central and sat on the board of EJA.137 As mentioned in Chapter 6, Glore Forgan was the same firm used by William Casey in his business ventures related to Multiponics.

The Penn Central link to EJA eventually emerged when Lassiter attempted to obtain a certificate that would have allowed him to operate larger aircraft. The Civil Aeronautics Board, which had a previous ruling forbidding a railroad from controlling an air carrier, discovered the tie and determined that the railroad had put around $22 million into the company. They then blocked Lassiter’s request for the certificate and ordered the railroad to divest from EJA. Lassiter then proceeded as follows:

Since he was barred from using the larger jets for domestic operations, Lassiter leased them to International Air Bahama, a Lichtenstein corporation he had persuaded a number of foreign investors to organize, which offered cut-rate service between Nassau and Luxembourg. However, although money was being made, lease money wasn’t getting back to Executive Jet. The money Lassiter raised, said Tibbets, allowed him to live like a millionaire.”138

Despite the Civil Aeronautics Board’s ruling, Penn Central money continued to flow into EJA, albeit via a more convoluted route. This was reportedly made possible, according to the New York Times, by Lassiter arranging “dates” for the aforementioned Charles Hodge as well as David Bevan, Penn Central’s CFO, so that the two men would “continue the flow of railroad funds to Executive Jet.”139 Both Hodge and Bevan were on the EJA board. The Times goes on to quote an official complaint, which stated: “The steady flow of Penn Central money to Executive Jet was maintained by Lassiter’s procuring of young women to accompany Bevan and Hodge on various junkets in the United States and Europe.”140

Paul Tibbets was also quoted as saying that “A weakness for beautiful women contributed to his [Lassiter’s] problems, according to more than one magazine article that appeared while EJA’s difficulties were making headlines.”141 Lassiter reportedly maintained furnished apartments in New York City and elsewhere in the US, as well as foreign cities that included Rome, where some of these women would allegedly accompany him.

In 1970, Bruce Sundlun, the attorney on the EJA board of directors who first connected the company to Penn Central, raided EJA’s offices as the company began its descent. In the course of that raid, Sundlun reportedly came across “a large stack of color photographs” that showed Lassiter “in the company of various young women, all of them very pretty and amply endowed.”142

During inquiries about the collapse of Penn Central, as previously mentioned, the congressional hearings involved lines of questioning directed at Lassiter about the procurement of women for Bevan and Hodge, which was allegedly performed by J.H. Ricciardi. Ricciardi had testified in 1968 that he had procured these women “to relieve the pressure they were exerting on Mr. Lassiter to get the company into the black.”143 Ricciardi also sued EJA over fees he claimed were owed to him for his efforts to procure women, which Ricciardi said he did at Lassiter’s request. Lassiter denied Ricciardi’s allegations and accused Ricciardi of “blackmail.”144

In addition, at those same congressional hearings that followed Penn Central’s implosion, Congressman J.W. Wright Patman (D-TX) stated that EJA’s role in the Penn Central collapse raised “most serious questions about the involvement of the commercial banking industry in the strange and far-flung operations of Executive Jet Aviation […] Commercial banks made massive amounts of credit available to Executive Jet Aviation for what appeared to be highly questionable – if not at times illegal – activities.”145

After Penn Central’s 1970 collapse, it re-emerged in 1977, not as a railroad company, but as an “energy, recreation, and real estate company.”146 A year later, it was disclosed that corporate raider Saul Steinberg, mentioned in Chapters 8 and 9 and who had previously tried to acquire Robert Maxwell’s Pergamon Press, had obtained 7.9 percent of the new incarnation of Penn Central, which grew to 13 percent a year later.147 Cincinnati financier Carl Lindner Jr. obtained 30 percent of the company between 1981 and 1982, which included Steinberg’s position. Lindner became chairman of Penn Central in 1983.148 The broker for these trades was Drexel Burnham Lambert’s Michael Milken. Also involved was Randall Smith Jr., then at Bear Stearns who later went on to become a prominent “vulture capitalist.”149

Lindner Jr. was also, at the time, intimately involved in Meshulam Riklis’ Rapid-American, which – as mentioned in Chapter 2 – contained the remnants of Lewis Rosenstiel’s business interests.150 He was also seemingly connected to Jack DeVoe, the cocaine smuggler mentioned in Chapter 7, as DeVoe maintained his planes at a club and airstrip that Lindner owned.151 In addition, the year after Lindner became chairman of Penn Central, Lindner Jr. would be given the reins of United Brands, a company with CIA links, by Leslie Wexner’s “mentor” Max Fisher and his associates (see Chapter 13).

As for Executive Jet Aviation, it was foreclosed upon before reopening with Bruce Sundlun in charge. Paul Tibbets would return to the company around the same time and would succeed Sundlun as president in 1976. In 1984, with Tibbets still serving as president, EJA was acquired by Richard Santulli. Previously, Santulli had served as president of Goldman Sachs’ leasing division, which bought helicopters and airplanes and then leased them to companies. Santulli left in 1980 to create his own leasing company, RTS Capital Services.152 EJA became a subsidiary of RTS and was later renamed as NetJets. It was during this era of EJA that Lawrence King, of Franklin Scandal fame, became a “frequent user of EJA’s service”, which – as previously mentioned – brought him into close contact with EJA executives.153

In 1993, at least two EJA pilots were recruited by Leslie Wexner’s The Limited, or Lbrands. One of these pilots, Eric Black, had been an EJA pilot starting in 1988, then working for an EJA subsidiary in Miami – Executive Jet Management – transporting checks for the Federal Reserve. He returned to EJA’s Columbus location in 1993, before being hired as a pilot for The Limited in August 1993. Black is now the Lead Captain for Lbrands flights.154 Another pilot, Mike Crater, also joined The Limited from EJA, where he had worked since 1986, in August 1993.155

1993 was a curious time in the activities of The Limited, particularly as it relates to its air freight concerns. As will be detailed in Chapter 17, in May of that year, The Limited was courted by a company called Polar Air Cargo, which sought to install itself at the Rickenbacker airstrip, once home to the Air Force Base where Lassiter had been stationed when he created Executive Jet. Polar Air Cargo, as reported by the Columbus Dispatch, was a joint venture of NedMark Transportation, Polaris Aircraft Leasing Corporation, and the now infamous CIA-linked airline Southern Air Transport.156 At the time, more than half of Polar Air Cargo’s employees had formerly worked for Flying Tiger Line, which – as noted in Chapter 5 – was tied to Anna Chennault and Robert Keith Gray. Though Polar Air Cargo’s efforts would be for naught, The Limited, with direct input from Jeffrey Epstein, would be largely responsible for the relocation of Southern Air Transport to Rickenbacker in 1995.

_______________

Endnotes:

1 Nicholas Von Hoffman, Citizen Cohn, 1st ed (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 402.

2 Gabriel H. Sanchez, “29 Pictures That Show Just How Insane Studio 54 Really Was,” Buzz-Feed News, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ga ... -just-how- insane-studio-54-really-was.

3 Bob Colacello, “Studio 54’s Cast List: A Who’s Who of the 1970s Nightlife Circuit,” Vanity Fair, September 4, 2013, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/1996/03 ... nightclub- newyork-city.

4 Tate Delloye, “Roy Cohn: New Documentary Explores the Man Who Made Donald Trump,” Mail Online, March 14, 2019, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/articl ... /Roy-Cohn- Donald-Trumps-ruthless-homophobic-attorney-partied-Studio-54-died-AIDS.html.

5 Von Hoffman, Citizen Cohn, 403.

6 Von Hoffman, Citizen Cohn, 405-407.

7 Frank Rich, “Roy Cohn was the Original Donald Trump,” Intelligencer, April 29, 2018, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/04 ... al-donald- trump.html.

8 Rich, “Original Donald Trump.”

9 Rich, “Original Donald Trump.”

10 Rich, “Original Donald Trump.”

11 Barbara Walters’ name can be found in Epstein’s black book of contacts. See “Epstein’s Black Book,” https://epsteinsblackbook.com/names/barbara-walters; Rich, “Original Donald Trump.”

12 Alan Feuer, “Up From Politics, Almost,” New York Times, October 1, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/01/nyre ... most.html; Marie Brenner, “How Donald Trump and Roy Cohn’s Ruthless Symbiosis Changed America,” Vanity Fair, June 28, 2017, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/06 ... -roy-cohn- relationship.

13 Von Hoffman, Citizen Cohn, 414.

14 Von Hoffman, Citizen Cohn, 334.

15 Jeffrey Toobin, “The Dirty Trickster,” The New Yorker, May 23, 2008, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/ ... trickster; Mark Ames, “Behind the Scenes of the Donald Trump - Roger Stone Show,” Pando, August 11, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20190730062 ... 11/behind- scenes-donald-trump-roger-stone-show/.

16 Sam Roberts, “Thomas A. Bolan, Understated Force in New York Law, Dies at 92,” New York Times, May 17, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/16/nyre ... olan-dead- roy-cohn-law-partner.html.

17 Roberts, “Thomas A. Bolan,”; Wanda Carruthers, “Tom Bolan, Famed Attorney and Roy Cohn’s Law Partner, Dies,” Newsmax, May 14, 2017, https://www.newsmax.com/Newsfront/Tom- Bolan-dies-lawyer-conservative/2017/05/14/id/790052/.

18 “Donald Trump and Ghislaine Maxwell on Her Dad’s (Robert) Yacht in May 1989,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 17, 1989, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/9383143/donald-trump- and-ghislaine-maxwell-on/.

19 David Ingram, “Sex Claim Filing Against Dershowitz a Mistake, Say Florida Lawyers; Defamation Claims Settled,” Insurance Journal, April 12, 2016, https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/s ... 04808.htm; Victor Thorn, “Louis Freeh: The Cover-up Goes National,” American Free Press, June 22, 2012, https://americanfreepress.net/web-exclu ... -national/.

20 Carruthers, “Tom Bolan,”; Marcus Baram, “Eavesdropping on Roy Cohn and Donald Trump,” The New Yorker, April 14, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/news/news- desk/eavesdropping-on-roy-cohn-and-donald-trump.

21 Baram, “Eavesdropping.”

22 Baram, “Eavesdropping.”

23 Baram, “Eavesdropping.”

24 Becky Little, “Roy Cohn: From Ruthless ‘Red Scare’ Prosecutor to Donald Trump’s Mentor,” HISTORY, March 6, 2019, https://www.history.com/news/roy-cohn-m ... rosenberg- trial-donald-trump.

25 James Michael Nichols, “Hillary Clinton Apologizes After Shocking Praise For Nancy Reagan’s ‘AIDS Activism,’” HuffPost, March 11, 2016, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hillary-clinton- nancy-reagan-aids-activism_n_56e31770e4b0b25c9181e002.

26 Robert Parry, “How Roy Cohn Helped Rupert Murdoch,” Consortium News, January 28, 2015, https://consortiumnews.com/2015/01/28/h ... t-murdoch/.

27 Jerry Oppenheimer, “President Reagan’s Mafia Ties Revealed in Explosive New Documentary,” Mail Online, May 21, 2014, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article- 2635094/EXCLUSIVE-Revealed-MAFIA-helped-Ronald-Reagan-White-House-Shocking- documentary-reveals-Mob-connections-catapulted-presidency-probe-thwarted-highest- levels.html.

28 Oppenheimer, “President Reagan’s Mafia Ties,”; Tina Daunt, “New Doc Alleges Ronald Reagan Blocked Probe Into Lew Wasserman’s Mafia Ties,” The Hollywood Reporter, June 12, 2014, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/ ... es-ronald- reagan-711288/.

29 Oppenheimer, “President Reagan’s Mafia Ties.”

30 Oppenheimer, “President Reagan’s Mafia Ties.”

31 Carl Sifakis, The Mafia Encyclopedia, 3. ed (New York: Checkmark Books, 2005), 132.

32 Mike Barnes, “Edie Wasserman, Wife of Lew Wasserman, Dies at 95,” The Hollywood Reporter, August 18, 2011, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/ ... news/edie- wasserman-wife-lew-wasserman-225101/.

33 Gus Russo, Supermob: How Sidney Korshak And His Criminal Associates Became America’s Hidden Power Brokers (New York: Bloomsbury, 2008), 158.

34 New West, Volume 1, p. 27, https://www.google.com/books/edition/New_West/6Sk- cAQAAIAAJ.

35 Nick Tosches, “The Man Who Kept The Secrets,” Vanity Fair, April 6, 1997, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/1997/04 ... he-Secrets.

36 Oppenheimer, “President Reagan’s Mafia Ties.”

37 David Cay Johnston, “Just What Were Donald Trump’s Ties to the Mob?,” POLITICO Magazine, May 22, 2016, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story ... rump-2016- mob-organized-crime-213910.

38 Newsweek Staff, “The Bcci-Cia Connection: Just How Far Did It Go?,” Newsweek, December 6, 1992, https://www.newsweek.com/bcci-cia-conne ... -go-195454.

39 Susan Trento, “Lord of the Lies; How Hill and Knowlton’s Robert Gray Pulls Washington’s Strings,” Washington Monthly, September 1, 1992, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Lord+of+ ... a012529888

40 “B’nai B’rith Testimonial Dinner in Honor of Roy Cohn,” May 2, 1983, https://consortiumnews.com/wp-content/u ... Dinner.pdf.

41 “B’Nai B’rith Dinner.”

42 “B’Nai B’rith Dinner.”

43 “The Order of B’Nai B’rith,” New York Times, March 31, 1878.

44 Bruce Weber, “He Relit Broadway: Gerald Schoenfeld Dies at 84,” New York Times, November 25, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/26/thea ... nfeld.html.

45 Barbara Gamarekian, “Washington Talk: Career Secretaries; Wielding Power Discreetly,” New York Times, May 14, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/14/us/w ... lk-career- secretaries-wielding-power-discreetly.html.

46 Jonathan Marshall, Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy: From Truman to Trump, ePub, (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc, 2021), 245.

47 Dan E. Moldea, Interference: How Organized Crime Influences Professional Football, 1st ed (New York: Morrow, 1989), 93–95, 451 note 8.

48 E. J. Dionne Jr, “US Envoy Denies Discussing Iran Arms,” New York Times, December 1, 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/12/01/worl ... -arms.html.

49 Robert D. McFadden, “Edward V. Regan, Longtime New York State Comptroller, Dies at 84,” New York Times, October 19, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/19/nyregion/edward- v-regan-longtime-new-york-state-comptroller-dies-at-84-.html.

50 “Rev. Bruce N. Ritter,”Bishop Accountability.org, https://www.bishop- accountability.org/assign/Ritter_Bruce_N_ofm.conv.htm.

51 Tracy Connor, “Scandal-Scarred Founder of Covenant House Dead at 72,” New York Post, October 12, 1999, https://nypost.com/1999/10/12/scandal-s ... -covenant- house-dead-at-72/.

52 Steve Cuozzo, “This NYC Priest’s Dramatic Downfall Was Just the Beginning of Perv-Priest Scandals,” New York Post, September 13, 2018, https://nypost.com/2018/09/13/this-nyc- priests-dramatic-downfall-was-just-the-beginning-of-perv-priest-scandals/.

53 Cuozzo, “Priest’s Dramatic Downfall.”

54 Cuozzo, “Priest’s Dramatic Downfall.”

55 M. A. Farber, “Ritter Inquiry Leading Many To Quit Board,” New York Times, May 1, 1990, https://www.nytimes.com/1990/05/01/nyre ... y-to-quit- board.html.

56 Cuozzo, “Priest’s Dramatic Downfall.”

57 Anthony Ramirez, “Rev. Bruce Ritter, 72, the Founder of Covenant House for Runaway Children,” New York Times, October 13, 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/13/nyre ... ounder-of- covenant-house-for-runaway-children.html.

58 Kroll Associates’ role is discussed in detail in Peter J. Wosh, Covenant House: Journey of a Faith-Based Charity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 184-88, 192, 207- 210.

It is also mentioned in New York Magazine. Christopher Byron, “High Spy,” New York Magazine, May 13, 1991, 72, https://books.google.cl/books?id=COkCAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA72.

59 “Limited hangout” is intelligence jargon for a form of propaganda in which a selected portion of a scandal, criminal act, sensitive or classified information, etc. is revealed or leaked, but avoids telling the whole story. This may be done to establish one’s credibility as a critic of something or somebody by engaging in criticism of them while, in fact, they are aiding the covering up by omitting more damaging details. Other motives may include the intention to distance oneself publicly from something using innocuous or vague criticism even when ones own sympathies are privately with them; or to divert public attention away from a more heinous act by leaking information about something less heinous. Byron, “High Spy,”; Kurt Eichenwald, “Drexel Burnham Fights Back,” New York Times, September 11, 1988, https://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/11/busi ... -back.html.

60 Charles M Sennott, Broken Covenant (New York: Windsor Pub., 1994), 14, https://archive.org/details/brokencovenant00senn.

61 Cuozzo, “Priest’s Dramatic Downfall.”

62 Ann Marsh, “Americares’ Success Hailed, Criticized,” Hartford Courant, August 10, 1991, https://www.courant.com/news/connecticu ... story.html.

63 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

64 Cuozzo, “Priest’s Dramatic Downfall.”

65 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

66 Farber, “Ritter Inquiry.”

67 Staff, “Rev. Bruce Ritter, 72, Founder of Covenant House, Dies,” Buffalo News, October 12, 1999, https://buffalonews.com/news/rev-bruce- ... ant-house- dies/article_5d8b7652-4204-599a-9507-2eefadc9aea6.html.

68 “Cryptonym: ZRSIGN,” Mary Ferrell Foundation, https://www.maryferrell.org/php/cryptdb ... rch=AIFLD; “United Fruit- C.I.A. Link Charged,” New York Times, October 22, 1976, https://www.nytimes.com/1976/10/22/arch ... arged.html.

69 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

70 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

71 Bill Flood, “Connecticut Reacts to Loss of ‘Native Son’, 41st U.S. President George H.W. Bush,” fox61.com, December 1, 2018, https://www.fox61.com/article/news/loca ... nnecticut- reacts-to-loss-of-native-son-41st-u-s-president-george-h-w-bush/520-0270014d-288b- 4da7-bd12-3c60188a2a76.

72 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

73 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

74 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

75 Marsh, “Americares’ Success.”

76 Matthew Phelan, “Seymour Hersh and the Men Who Want Him Committed,” Salon, February 28, 2011, https://www.salon.com/2011/02/28/seymou ... howhatwhy/.

77 Kris Hundley and Kendall Taggart, “No Accounting for $40 Million in Charity Shipped Over- seas,” Tampa Bay Times, https://www.tampabay.com/news/business/ ... ng-for-40- million-in-charity-shipped-overseas/2162553/.

78 Phelan, “Seymour Hersh.”

79 John W. DeCamp, The Franklin Cover-Up: Child Abuse, Satanism, and Murder in Nebraska (Lincoln, Neb: AWT, 1992), 180.

80 Deborah Sontag, “L.I. Man Who Runs Home for Boys In Guatemala Is on Trial in Absentia,” New York Times, April 12, 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/12/nyregion/li-man- who-runs-home-for-boys-in-guatemala-is-on-trial-in-absentia.html.

81 Nicholas A. Bryant, The Franklin Scandal: A Story of Powerbrokers, Child Abuse and Betrayal, First edition (revised for softcover) (Waterville, OR: Trine Day, 2012), 32–33.

82 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 35-36

83 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 36.

84 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 36-37.

85 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 37-38.

86 Robert Dorr, “King Donated $25,350 to Aid Lobbying Group,” Omaha World Herald, May 21, 1989.

87 For more information see: Pete Brewton, The Mafia, CIA, and George Bush (S.P.I. Books, Dec. 1992).

88 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 37.

89 Dorr, “King Donated $23,500.”

90 Dorr, “King Donated $23,500.”

91 Harry Bernstein, “Former CIA Man Now Battling Unions,” Los Angeles Times, February 18, 1987, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm ... story.html.

92 Dorr, “King Donated $23,500.”

93 Max Fisher, “Letter to Morris Lasker,” September 28, 1987, https://www.sechistorical.org/collectio ... Boesky.pdf.

94 “Wall Street’s Top Earners: Your Pain, Their Gain,” Forbes, April 15, 2008, https://www.forbes.com/2008/04/15/pauls ... -biz-wall- cz_js_0415wallstreet.html.

95 Dorr, “King Donated $23,500.”

96 Dorr, “King Donated $23,500.”

97 Warwick Middleton, MD, “An Interview with Nick Bryant: Part I – The Franklin Scandal,” August 7, 2019, https://news.isst-d.org/an-interview-wi ... -franklin- scandal/.

98 William Robbins, “A Lurid, Mysterious Scandal Begins Taking Shape in Omaha,” New York Times, December 18, 1988, https://www.nytimes.com/1988/12/18/us/a ... ysterious- scandal-begins-taking-shape-in-omaha.html.

99 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 87.

100 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 98.

101 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 158.

102 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 158-59.

103 Robbins, “Scandal in Omaha.”

104 Patrick Wood, “Flashback - How The Trilateral Commission Converted China Into A Technocracy,” Technocracy News, April 22, 2016, https://www.technocracy.news/trilateral- commission-converted-china-technocracy/.

105 “Joseph S Nye Resume,” https://apps.hks.harvard.edu/faculty/cv/JosephNye.pdf.

106 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 280-84.

107 Phil Gailey, “Have Names, Will Open Right Doors,” New York Times, January 18, 1982, https://www.nytimes.com/1982/01/18/us/h ... doors.html.

108 Gailey, “Have Names.”

109 Gailey, “Have Names.”

110 Gailey, “Have Names.”

111 Lee Siegel, “In Short: Nonfiction,” New York Times, May 21, 1995, https://www.nytimes.com/1995/05/21/book ... 31795.html.

112 Jacob Shamsian, “John Glenn Was a Passenger on Jeffrey Epstein’s Private Jet in 1996, According to Unsealed Flight Records,” Insider, August 9, 2019, https://www.insider.com/john-glenn-flew ... jet-2019-8.

113 Michael Hedges and Jerry Seper, “Power Broker Served Drugs, Sex at Parties Bugged for Blackmail,” Washington Times, June 30, 1989, sec. Final.

114 John W. DeCamp, The Franklin Cover-Up: Child Abuse, Satanism, and Murder in Nebraska, ePub (Nebraska: AWT, 1992), 169.

115 Hedges and Seper, “Power Broker Served Drugs.”

116 Hedges and Seper, “Power Broker Served Drugs.”

117 Hedges and Seper, “Power Broker Served Drugs.”

118 Paul M Rodriguez and George Archibald, “Homosexual Prostitution Inquiry Ensnares VIPs with Reagan, Bush ‘Call Boys’ Took Midnight Tour of White House,” Washington Times, June 29, 1989, https://govcrime.wordpress.com/2011/03/ ... y-article- 1989/.

119 Jerry Seper and Michael Hedges, “Spence Arrested in N.Y., Released; Once-Host to Powerful Reduced to Begging, Sleeping in Park,” Washington Times, August 9, 1989, https://govcrime.wordpress.com/2011/04/ ... once-host- to-powerful-reduced-to-begging-sleeping-in-park/.

120 “What the CIA Tells Congress (Or Doesn’t) about Covert Operations: The Barr/Cheney/Bush Turning Point for CIA Notifications to the Senate,” NSA Archive, February 7, 2019, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book ... -congress- or-doesnt-about-covert-operations-barrcheneybush-turning-point-cia.

121 Jack Anderson and Les Whitten, “CIA Love Traps Lured Diplomats,” Washington Post, February 5, 1975, http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/White%20 ... /Security- CIA/CIA%201025.pdf.

122 Rodriguez and Archibald, “Homosexual Prostitution Inquiry.”

123 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 293, 295.

124 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 296.

125 Henry W. Vinson, Confessions of a D.C. Madam: The Politics of Sex, Lies & Blackmail, First Edition (Oregon: Trine Day, 2014), 118–19.

126 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 296-300.

127 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 284.

128 Bryant, Franklin Scandal, 296-97.

129 “Skybound Business Exec,” Jet, July 6, 1987, 28, https://books.google.com/books? id=_LEDAAAAMBAJ.

130 Joseph R Daughen and Peter Binzen, The Wreck of the Penn Central, First edition (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1971), 202-04, https://archive.org/details/wreckofpenncentr00daug.

131 “Paul Tibbets: A Rendezvous with History (Part 3),” Airport Journals, June 1, 2003, http://airportjournals.com/paul-tibbets ... ry-part-3/.

132 “Paul Tibbets.”

133 “Paul Tibbets.”

134 “Paul Tibbets.”

135 John J. McCloy, chairman of the Rockefeller-dominated Chase Manhattan Bank, became an ‘important financial ally’ of Clint Murchison, Sr., and Sid Richardson when the two Texans became (through Alleghany Corp.) major stockholders in the New York Central Railroad, later merged into Penn Central.” See Peter Dale Scott, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (University of California Press, 1996), 136.

In addition, the founder of Alleghany and the architect of its takeover of New York Central via the use of Richardson and Murchison as proxies, Robert R. Young, was a client of the Baird Foundation. “...Mr. Young disclosed that Mr. David G. Baird, ‘a good friend of his, had approached the [Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad] to sell its Central stock to an investing group before it sold the block to Messrs. Murchison and Richardson’” See: Tax-Exempt Foundations and Charitable Trusts, Their Impact on Our Economy: United States House Select Committee on Small Business, 1963, 57-58.

Penn Central money was put into Great Southwest via Penphil, a private investment operation set up by the railroad’s CFO David Bevan and General Charles J. Hodge, the railroad’s chief investment officer. See: Associated Press, “$21-Million Fraud.” “...control of Great Southwest was tightly centered in the Rockefeller and Wynne families” See: The Penn Central Failure and the Role of Financial Institutions: Staff Report of the Committee on Banking and Currency, 1970, 30.

136 Scott, Deep Politics, 284.

137 Daughen and Blinzen, The Wreck of Penn Central, 161.

138 “Paul Tibbets.”

139 The Associated Press, “$21-Million Fraud Al Penn Central Is Charged to 3,” New York Times, January 5, 1972, https://www.nytimes.com/1972/01/05/arch ... d-at-penn- central-is-charged-to-3-bevan-exfinance.html.

140 AP, “$21-Million Fraud.”

141 “Paul Tibbets.”

142 Daughen and Blinzen, The Wreck of Penn Central, 176.

143 Michael C. Jensen, “Pennsy Is Scored in a House Report,” New York Times, December 21, 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/21/arch ... se-report- jet-aviation-units-history.html.

144 Daughen and Blinzen, The Wreck of Penn Central, 204.

145 Jensen, “Pennsy is Scored.”

146 Robert J Cole, “Saul Steinberg: Gunning for Penn Central,” New York Times, November 11, 1979, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/11/11/arch ... -for-penn- central.html.

147 Cole, “Saul Steinberg.”

148 Daniel F. Cuff, “Business People; Lindner Chairman of Penn Central,” New York Times, May 20, 1983, https://www.nytimes.com/1983/05/20/busi ... -chairman- of-penn-central.html.

149 Hilary Rosenberg, The Vulture Investors (New York: J. Wiley, 2000), 12.

150 Cuff, “Business People.”

151 For DeVoe’s relationship to Ocean Reef, see: Organized Crime and Cocaine Trafficking Record of Hearing IV, President’s Commission on Organized Crime, November 27-29, 1984, https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-libra ... d-cocaine- trafficking. Additional corroboration can be found in Scott, Deep Politics, 335.

152 “How Richard Santulli Became The Father of Fractional Ownership,” International Aviation HQ, January 26, 2022, https://internationalaviationhq.com/202 ... -santulli- netjets/.

153 “Skybound Business Exec,” Jet.

154 Eric Black, LinkedIn, Accessed June 28, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/in/eric-black- 660a01126/details/experience/.

155 Mike Crater, LinkedIn, Accessed June 28, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/in/mike-crater- 2aa9316/.

156 “Cargo Service Targets City – Polar Plans to Land Weekly Flights at Rickenbacker Starting Sunday,” Columbus Dispatch, May 12, 1993, https://dispatch.newsbank.com/doc/news/10E0D9C54B7D92F8.