Part 2 of 3

With this in mind, the Company realised that if it was to trade successfully with the Mughals, it would need both partners and permissions, which meant establishing a relationship with the Mughal Emperor himself. It took Hawkins a year to reach Agra, which he managed to do dressed as an Afghan nobleman. Here he was briefly entertained by the Emperor, with whom he conversed in Turkish, before Jahangir lost interest in the semi-educated sea dog and sent him back home with the gift of an Armenian Christian wife. The mission achieved little, and soon afterwards another EIC fleet, captained by Sir Henry Middleton, was driven away from the Surat anchorage of Suvali – or ‘Swally Hole’ as the English mangled it – by local officials who ordered him to leave after threats from the Portuguese residents in the port.51

A new, more impressive mission was called for, and this time the Company persuaded King James to send a royal envoy. The man chosen was a courtier, MP, diplomat, Amazon explorer, Ambassador to the Sublime Porte and self-described ‘man of quality’, Sir Thomas Roe.52 In 1615 Roe finally arrived in Ajmer, bringing presents of ‘hunting dogges’ – English mastiffs and Irish greyhounds – an English state coach, some Mannerist paintings, an English virginal and many crates of red wine for which he had heard Jahangir had a fondness; but Roe nevertheless had a series of difficult interviews with the Emperor. When he was finally granted an audience, and had made his obeisance, Roe wanted immediately to get to the point and raise the subject of trade and preferential customs duties, but the aesthete Emperor could barely conceal his boredom at such conversations.

Jahangir was, after all, an enormously sensitive, curious and intelligent man: observant of the world around him and a keen collector of its curiosities, from Venetian swords and globes to Safavid silks, jade pebbles and even narwhal teeth. A proud inheritor of the Indo-Mughal tradition of aesthetics and knowledge, as well as maintaining the Empire and commissioning great works of art, he took an active interest in goat and cheetah breeding, medicine and astronomy, and had an insatiable appetite for animal husbandry, like some Enlightenment landowner of a later generation.

This, not the mechanics of trade, was what interested him, and there followed several months of conversations with the two men talking at cross purposes. Roe would try to steer the talk towards commerce and diplomacy and the firmans (imperial orders) he wanted confirming ‘his favour for an English factory’ at Surat and ‘to establish a firm and secure Trade and residence for my countrymen’ in ‘constant love and pease’; but Jahangir would assure him such workaday matters could wait, and instead counter with questions about the distant, foggy island Roe came from, the strange things that went on there and the art which it produced. Roe found that Jahangir ‘expects great presents and jewels and regards no trade but what feeds his insatiable appetite after stones, riches and rare pieces of art’.53

‘He asked me what Present we would bring him,’ Roe noted. I answered the league [between England and Mughal India] was yet new, and very weake: that many curiosities were to be found in our Countrey of rare price and estimation, which the king would send, and the merchants seeke out in all parts of the world, if they were once made secure of a quiet trade and protection on honourable Conditions.

He asked what those curiosities were I mentioned, whether I meant jewels and rich stones. I answered No: that we did not thinke them fit Presents to send backe, which were first brought from these parts, whereof he was the Chiefe Lord … but that we sought to find things for his Majestie, as were rare here, and vnseene. He said it was very well: but that he desired an English horse … So with many passages of jests, mirth, and bragges concerning the Arts of his Countrey, he fell to ask me questions, how often I drank a day, and how much, and what? What in England? What beere was? How made? And whether I could make it here. In all which I satisfied his great demands of State …54

Roe could on occasion be dismissively critical of Mughal rule – ‘religions infinite, laws none’ – but he was, despite himself, thoroughly dazzled. In a letter describing the Emperor’s birthday celebrations in 1616, written from the beautiful, half-ruined hilltop fortress of Mandu in central India to the future King Charles I in Whitehall, Roe reported that he had entered a world of almost unimaginable splendour.

The celebrations were held in a superbly designed ‘very large and beautifull Garden, the square within all water, on the sides flowres and trees, in the midst a Pinacle, where was prepared the scales … of masse gold’ in which the Emperor would be weighed against jewels.

Here attended the Nobilitie all sitting about it on Carpets until the King came; who at least appeared clothed, or rather laden with Diamonds, Rubies, Pearles, and other precious vanities, so great, so glorious! His head, necke, breast, armes, above the elbowes, at the wrists, his fingers each one with at least two or three Rings, are fettered with chaines of dyamonds, Rubies as great as Walnuts – some greater – and Pearles such as mine eyes were amazed at … in jewells, which is one of his felicityes, hee is the treasury of the world, buyeing all that comes, and heaping rich stones as if hee would rather build [with them] than wear them.55

The Mughals, in return, were certainly curious about the English, but hardly overwhelmed. Jahangir greatly admired an English miniature of one of Roe’s girlfriends – maybe the Lady Huntingdon to whom he wrote passionately from ‘Indya’.56 But Jahangir made a point of demonstrating to Roe that his artists could copy it so well that Roe could not tell copy from original. The English state coach was also admired, but Jahangir had the slightly tatty Tudor interior trim immediately upgraded with Mughal cloth of gold and then again showed off the skills of the Mughal kar-khana by having the entire coach perfectly copied, in little over a week, so his beloved Empress, Nur Jahan, could have a coach of her own.57

Meanwhile, Roe was vexed to discover that the Mughals regarded relations with the English as a very low priority. On arrival he was shoved into a substandard accommodation: only four caravanserai rooms allotted for the entire embassy and they ‘no bigger than ovens, and in that shape, round at the top, no light but the door, and so little that the goods of two carts would fill them all’.58 More humiliatingly still, his slightly shop-soiled presents were soon completely outshone by those of a rival Portuguese embassy who gave Jahangir ‘jewels, Ballests [balas spinels] and Pearles with much disgrace to our English commoditie’.59

When Roe eventually returned to England, after three weary years at court, he had obtained permission from Jahangir to build a factory (trading station) in Surat, an agreement ‘for our reception and continuation in his domynyons’ and a couple of imperial firmans, limited in scope and content, but useful to flash at obstructive Mughal officials. Jahangir, however, made a deliberate point of not conceding any major trading privileges, possibly regarding it as beneath his dignity to do so.60

The status of the English at the Mughal court in this period is perhaps most graphically illustrated by one of the most famous images of the period, a miniature by Jahangir’s master artist, Bichitr. The conceit of the painting is how the pious Jahangir preferred the company of Sufis and saints to that of powerful princes. This was actually not as far-fetched as it might sound: one of Roe’s most telling anecdotes relates how Jahangir amazed the English envoy by spending an hour chatting to a passing holy man he encountered on his travels:

a poor silly old man, all asht, ragd and patcht, with a young roague attending on him. This miserable wretch cloathed in rags, crowned with feathers, his Majestie talked with about an hour, with such familiaritie and shew of kindnesse, that it must needs argue an humilitie not found easily among Kings … He took him up in his armes, which no cleanly body durst have touched, imbracing him, and three times laying his hand on his heart, calling him father, he left him, and all of us, and me, in admiration of such a virtue in a heathen Prince.61

Bichitr illustrates this idea by showing Jahangir centre frame, sitting on a throne with the halo of Majesty glowing so brightly behind him that one of the putti, caught in flight from a Portuguese transfiguration, has to shield his eyes from the brightness of his radiance; another pair of putti are writing a banner reading ‘Allah Akbar! Oh king, may your age endure a thousand years!’ The Emperor turns to hand a Quran to a cumulus-bearded Sufi, spurning the outstretched hands of the Ottoman Sultan. As for James I, in his jewelled and egret-plumed hat and silver-white Jacobean doublet, he is relegated to the bottom left corner of the frame, below Jahangir’s feet and only just above Bichitr’s own self-portrait. The King shown in a three-quarter profile – an angle reserved in Mughal miniatures for the minor characters – with a look of vinegary sullenness on his face at his lowly place in the Mughal hierarchy.62 For all the reams written by Roe on Jahangir, the latter did not bother to mention Roe once in his voluminous diaries. These awkward, artless northern traders and supplicants would have to wait a century more before the Mughals deigned to take any real interest in them.

Yet for all its clumsiness, Roe’s mission was the beginning of a Mughal– Company relationship that would develop into something approaching a partnership and see the EIC gradually drawn into the Mughal nexus. Over the next 200 years it would slowly learn to operate skilfully within the Mughal system and to do so in the Mughal idiom, with its officials learning good Persian, the correct court etiquette, the art of bribing the right officials and, in time, outmanoeuvring all their rivals – Portuguese, Dutch and French – for imperial favour. Indeed, much of the Company’s success at this period was facilitated by its scrupulous regard for Mughal authority.63 Before long, indeed, the Company would begin portraying itself to the Mughals, as the historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam has nicely described it, as ‘not a corporate entity but instead an anthropomorphized one, an Indo-Persian creature called Kampani Bahadur’.64

[x]

On his return to London, Roe made it clear to the directors that force of arms was not an option when dealing with the Mughal Empire. ‘A warre and traffic,’ he wrote, ‘are incompatible.’ Indeed he advised against even fortified settlements and pointed out how ‘the Portuguese many rich residences and territoryes [were] beggaring’ their trade with unsupportable costs. Even if the Mughals were to allow the EIC a fort or two, he wrote, ‘I would not accept one … for without controversy it is an errour to affect garrisons and land warrs in India.’ Instead he recommended: ‘Lett this be received as a rule, that if you will seek profit, seek it at sea and in a quiett trade.’65

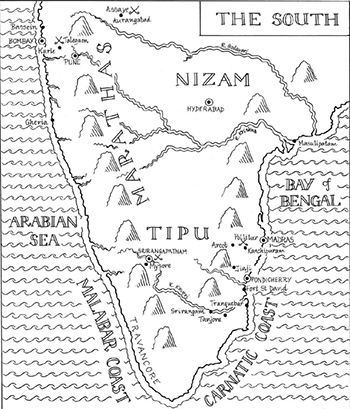

To begin with, the Company took his advice. Early EIC officials prided themselves on negotiating commercial privileges, rather than resorting to attacking strategic ports like the more excitable Portuguese, and it proved to be a strategy that paid handsome dividends. While Roe was busy charming Jahangir, another Company emissary, Captain Hippon, was despatched on the Globe to open the textile trade with the eastward-facing Coromandel coast and to establish a second factory at Masulipatnam, the port of the Mughal’s great Deccani rivals, the diamond-rich Sultanate of Golconda, where could be bought the finest jewels and chintz in India.66 A third factory dealing mainly with the trade in saltpetre – the active ingredient in gunpowder – opened shortly afterwards in Patna.

This trade in jewels, pepper, textiles and saltpetre soon resulted in even better returns than the Dutch trade in aromatic spices: by the 1630s the EIC was importing £1 million of pepper from India which, in a dramatic reversal of centuries of trading patterns, it now began exporting to Italy and the Middle East, through its sister the Levant Company. Thirty years later they were importing a quarter of a million pieces of cloth, nearly half of them from the Coromandel.67 Losses were still heavy: between 1601 and 1640, the Company sent a total of 168 ships eastwards; only 104 arrived back again.68 But the Company’s balance sheets grew increasingly profitable, so much so that investors from around Europe began for the first time queuing up to buy EIC stock. In 1613 the subscription for the First Joint Stock raised £418,000. Four years later, in 1617, the subscription to Second Joint Stock pulled in a massive £1.6 million,* turning the EIC for the first time into a financial colossus, at least by English standards.69 The success of the EIC in turn stimulated not only the London docks but also the nascent London stock exchange. By the middle of the century half of those who were elected to the elite Court of Aldermen of the City of London were either Levant Company traders or EIC directors, or both.70 One Company member, the early economic theorist Thomas Mun, wrote that the Company’s trade was now ‘the very touchstone of the Kingdom’s prosperity’.71

It was not until 1626 that the EIC founded its first fortified Indian base, at Armagon, north of Pulicat, on the central Coromandel coast. It was soon crenellated and armed with twelve guns. But it was quickly and shoddily constructed, in addition to which it was found to be militarily indefensible, so was abandoned six years later in 1632 with little regret; as one factor put it, ‘better lost than found’.72

Two years later, the EIC tried again. The head of the Armagon factory, Francis Day, negotiated with the local governor of what was left of the waning and fragmented South Indian Vijayanagara empire for the right to build a new EIC fort above a fishing village called Madraspatnam, just north of the Portuguese settlement at San Thome. Again, it was neither commercial nor military considerations which dictated the choice of site. Day, it was said, had a liaison with a Tamil lady whose village lay inland from Madraspatnam. According to one contemporary source Day ‘was so enamoured of her’ and so anxious that their ‘interviews’ might be ‘more frequent and uninterrupted’ that his selection of the site of Fort St George lying immediately adjacent to her home village was a foregone conclusion.73

This time the settlement – soon known simply as Madras – flourished. The Naik (governor) who leased the land said he was anxious for the area to ‘flourish and grow rich’, and had given Day the right to build ‘a fort and castle’, to trade customs free and to ‘perpetually Injoy the priviledges of minatag[e];’. These were major concessions that the more powerful Mughals to the north would take nearly another century to yield.

Initially, there were ‘only the French padres and about six fishermen, soe to intice inhabitants to people the place, a proclamation was made … that for a terme of thirty years’ no custom duties would be charged. Soon weavers and other artificers and traders began pouring in. Still more came once the fort walls had been erected, ‘as the tymes are turned upp syde downe’, and the people of the coast were looking for exactly the security and protection the Company could provide.74

Before long Madras had grown to be the first English colonial town in India with its own small civil administration, the status of a municipality and a population of 40,000. By the 1670s the town was even minting its own gold ‘pagoda’ coins, so named after the image of a temple that filled one side, with the monkey deity Hanuman on the reverse, both borrowed from the old Vijayanagara coinage.75

The second big English settlement in India came into the hands of the Company via the Crown, which in turn received it as a wedding present from the Portuguese monarchy. In 1661, when Charles II married the Portuguese Infanta, Catherine of Braganza, part of her dowry, along with the port of Tangier, was the ‘island of Bumbye’. In London there was initially much confusion as to its whereabouts, as the map which accompanied the Infanta’s marriage contract went missing en route. No one at court seemed sure where ‘Bumbye’ was, though the Lord High Chancellor believed it to be ‘somewhere near Brazil’.76

It took some time to sort out this knotty issue, and even longer to gain actual control of the island, as the Portuguese governor had received no instructions to hand it over, and so understandably refused to do so. When Sir Abraham Shipman first arrived with 450 men to claim Bombay for the English in September 1662, his mission was blocked at gunpoint; it was a full three years before the British were finally able to take over, by which time the unfortunate Shipman, and all his officers bar one, had died of fever and heatstroke, waiting on a barren island to the south. When Shipman’s secretary was finally allowed to land on Bombay island in 1665, only one ensign, two gunners and 111 subalterns were still alive to claim the new acquisition.77

Despite this bumpy start, the island soon proved its worth: the Bombay archipelago turned out to have the best natural harbour in South Asia, and it quickly became the Company’s major naval base in Asia, with the only dry dock where ships could be safely refitted during the monsoon. Before long it had eclipsed Surat as the main centre of EIC operations on the west coast, especially as the rowdy English were becoming less and less welcome there: ‘Their private whorings, drunkenesse and such like ryotts … breaking open whorehouses and rackehowses [i.e. arrack bars] have hardened the hearts of the inhabitants against our very names,’ wrote one weary EIC official. Little wonder that the British were soon being reviled in the Surat streets ‘with the names of Ban-chude* and Betty-chude† which my modest language will not interpret’.78

Within thirty years Bombay had grown to house a colonial population of 60,000 with a growing network of factories, law courts, an Anglican church and large white residential houses surrounding the fort and tumbling down the slope from Malabar Hill to the Governor’s estate on the seafront. It even had that essential amenity for any God-fearing seventeenth-century Protestant community, a scaffold where ‘witches’ were given a last chance to confess before their execution.79 It also had its own small garrison of 300 English soldiers, ‘400 Topazes, 500 native militia and 300 Bhandaris [club-wielding toddy-tappers] that lookt after the woods of cocoes’. By the 1680s Bombay had briefly eclipsed Madras ‘as the seat of power and trade of the English in the East Indies’.80

Meanwhile, in London, the Company directors were beginning to realise for the first time how powerful they were. In 1693, less than a century after its foundation, the Company was discovered to be using its own shares for buying the favours of parliamentarians, as it annually shelled out £1,200 a year to prominent MPs and ministers. The bribery, it turned out, went as high as the Solicitor General, who received £218, and the Attorney General, who received £545.** The parliamentary investigation into this, the world’s first corporate lobbying scandal, found the EIC guilty of bribery and insider trading and led to the impeachment of the Lord President of the Council and the imprisonment of the Company’s Governor.

Only once during the seventeenth century did the Company try to use its strength against the Mughals, and then with catastrophic consequences. In 1681 the directorship was taken over by the recklessly aggressive Sir Josiah Child, who had started his career supplying beer to the navy in Portsmouth, and who was described by the diarist John Evelyn as ‘an overgrown and suddenly monied man … most sordidly avaricious’.81 In Bengal the factors had begun complaining, as Streynsham Master wrote to London, that ‘here every petty Officer makes a pray of us, abuscing us at pleasure to Screw what they can out of us’. We are, he wrote, ‘despised and trampled upon’ by Mughal officials. This was indeed the case: the Nawab of Bengal, Shaista Khan, made no secret of his dislike of the Company and wrote to his friend and maternal nephew, the Emperor Aurangzeb, that ‘the English were a company of base, quarrelling people and foul dealers’.82

Ignorant of the scale of Mughal power, Child made the foolish decision to react with force and attempt to teach the Mughals a lesson: ‘We have no remedy left,’ he wrote from the Company’s Court in Leadenhall Street, ‘but either to desert our trade, or we must draw the sword his Majesty has Intrusted us with, to vindicate the Rights and Honor of the English Nation in India.’83 As a consequence, in 1686 a considerable fleet sailed from London to Bengal with 19 warships, 200 cannons and 600 soldiers. ‘It will,’ Child wrote, ‘become us to Seize what we cann & draw the English sword.’84

But Child could not have chosen a worse moment to pick a fight with the Emperor of the richest kingdom on earth. The Mughals had just completed their conquest of the two great Deccani Sultanates of Bijapur and Golconda and seemed also to have driven the Marathas back into the hills whence they had come. The Mughal Empire had thus emerged as the unrivalled regional power, and its army was now able to focus exclusively on this new threat. The Mughal war machine swept away the English landing parties as easily as if it were swatting flies; soon the EIC factories at Hughli, Patna, Kasimbazar, Masulipatnam and Vizagapatam had all been seized and plundered, and the English had been expelled completely from Bengal. The Surat factory was closed and Bombay was blockaded.

The EIC had no option but to sue for peace and beg for the return of its factories and hard-earned trading privileges. They also had to petition for the release of its captured factors, many of whom were being paraded in chains through the streets or kept fettered in the Surat castle and the Dhaka Red Fort ‘in insufferable and tattered conditions … like thiefs and murders’.85 When Aurangzeb heard that the EIC had ‘repented of their irregular proceedings’ and submitted to Mughal authority, the Emperor left the factors to lick their wounds for a while, then in 1690 graciously agreed to forgive them.

It was in the aftermath of this fiasco that a young factor named Job Charnock decided to found a new British base in Bengal to replace the lost factories that had just been destroyed. On 24 August 1690, with ‘ye rains falling day and night’, Charnock began planting his settlement on the swampy ground between the villages of Kalikata and Sutanuti, adjacent to a small Armenian trading station, and with a Portuguese one just across the river.

Job Charnock bought the future site of Calcutta, said the Scottish writer Alexander Hamilton, ‘for the sake of a large shady tree’, an odd choice, he thought, ‘for he could not have found a more unhealthful Place on all the River’.86 According to Hamilton’s New Account of the East Indies: ‘Mr Channock choosing the Ground of the Colony, where it now is, reigned more absolute than a Rajah’:

The country about being overspread with Paganism, the Custom of Wives burning with their deceased Husbands is also practised here. Mr Channock went one Time with his guard of Soldiers, to see a young widow act that tragical Catastrophe, but he was so smitten with the Widow’s Beauty, that he sent his guards to take her by Force from her Executioners, and conducted her to his own Lodgings. They lived lovingly many Years, and had several children. At length she died, after he had settled in Calcutta, but instead of converting her to Christianity, she made him a Proselyte to Paganism, and the only Part of Christianity that was remarkable in him, was burying her decently, and he built a Tomb over her, where all his Life after her Death, he kept the anniversary Day of her Death by sacrificing a Cock on her Tomb, after the Pagan Manner.87

Mrs Charnock was not the only fatality. Within a year of the founding of the English settlement at Calcutta, there were 1,000 living in the settlement but already Hamilton was able to count 460 names in the burial book: indeed, so many died there that it is ‘become a saying that they live like Englishmen and die like rotten sheep’.88

Only one thing kept the settlement going: Bengal was ‘the finest and most fruitful country in the world’, according to the French traveller François Bernier. It was one of ‘the richest most populous and best cultivated countries’, agreed the Scot Alexander Dow. With its myriad weavers – 25,000 in Dhaka alone – and unrivalled luxury textile production of silks and woven muslins of fabulous delicacy, it was by the end of the seventeenth century Europe’s single most important supplier of goods in Asia and much the wealthiest region of the Mughal Empire, the place where fortunes could most easily be made. In the early years of the eighteenth century, the Dutch and English East India Companies between them shipped into Bengal cargoes worth around 4.15 million rupees* annually, 85 per cent of which was silver.89

The Company existed to make money, and Bengal, they soon realised, was the best place to do it.

[x]

It was the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 that changed everything for the Company.

The Emperor, unloved by his father, grew up into a bitter and bigoted Islamic puritan, as intolerant as he was grimly dogmatic. He was a ruthlessly talented general and a brilliantly calculating strategist, but entirely lacked the winning charm of his predecessors. His rule became increasingly harsh, repressive and unpopular as he grew older. He made a clean break with the liberal and inclusive policies towards the Hindu majority of his subjects pioneered by his great-grandfather Akbar, and instead allowed the ulama to impose far stricter interpretations of Sharia law. Wine was banned, as was hashish, and the Emperor ended his personal patronage of musicians. He also ended Hindu customs adopted by the Mughals such as appearing daily to his subjects at the jharoka palace window in the centre of the royal apartments in the Red Fort. Around a dozen Hindu temples across the country were destroyed, and in 1672 he issued an order recalling all endowed land given to Hindus and reserved all future land grants for Muslims. In 1679 the Emperor reimposed the jizya tax on all non-Muslims that had been abolished by Akbar; he also executed Teg Bahadur, the ninth of the gurus of the Sikhs.90

While it is true that Aurangzeb is a more complex and pragmatic figure than some of his critics allow, the religious wounds Aurangzeb opened in India have never entirely healed, and at the time they tore the country in two.* Unable to trust anyone, Aurangzeb marched to and fro across the Empire, viciously putting down successive rebellions by his subjects. The Empire had been built on a pragmatic tolerance and an alliance with the Hindus, especially with the warrior Rajputs, who formed the core of the Mughal war machine. The pressure put on that alliance and the Emperor’s retreat into bigotry helped to shatter the Mughal state and, on Aurangzeb’s death, it finally lost them the backbone of their army.

But it was Aurangzeb’s reckless expansion of the Empire into the Deccan, largely fought against the Shia Muslim states of Bijapur and Golconda, that did most to exhaust and overstretch the resources of the Empire. It also unleashed against the Mughals a new enemy that was as formidable as it was unexpected. Maratha peasants and landholders had once served in the armies of the Bijapur and Golconda. In the 1680s, after the Mughals conquered these two states, Maratha guerrilla raiders under the leadership of Shivaji Bhonsle, a charismatic Maratha Hindu warlord, began launching attacks against the Mughal armies occupying the Deccan. As one disapproving Mughal chronicler noted, ‘most of the men in the Maratha army are unendowed with illustrious birth, and husbandmen, carpenters and shopkeepers abound among their soldiery’.91 They were largely armed peasants; but they knew the country and they knew how to fight.

From the sparse uplands of the western Deccan, Shivaji led a prolonged and increasingly widespread peasant rebellion against the Mughals and their tax collectors. The Maratha light cavalry, armed with spears, were remarkable for their extreme mobility and the ability to make sorties far behind Mughal lines. They could cover fifty miles in a day because the cavalrymen carried neither baggage nor provisions and instead lived off the country: Shivaji’s maxim was ‘no plunder, no pay’.92 One Jacobean traveller, Dr John Fryer of the EIC, noted that the ‘Naked, Starved Rascals’ who made up Shivaji’s army were armed with ‘only lances and long swords two inches wide’ and could not win battles in ‘a pitched Field’, but were supremely skilled at ‘Surprising and Ransacking’.93

According to Fryer, Shivaji’s Marathas sensibly avoided pitched battles with the Mughal’s army, opting instead to ravage the centres of Mughal power until the economy collapsed. In 1663, Shivaji personally led a daring night raid on the palace of the Mughal headquarters in Pune, where he murdered the family of the Governor of the Deccan, Aurangzeb’s uncle, Shaista Khan. He also succeeded in cutting off the Governor’s finger.94 In 1664, Shivaji’s peasant army raided the Mughal port of Surat, sacking its richly filled warehouses and extorting money from its many bankers. He did the same in 1670, and by the Marathas’ third visit in 1677 there was not even a hint of resistance.

In between the last two raids, Shivaji received, at his spectacular mountain fastness of Raigad, a Vedic consecration and coronation by the Varanasi pandit Gagabhatta, which was the ritual highlight of his career. This took place on 6 June 1674 and awarded him the status of the Lord of the Umbrella, Chhatrapati, and legitimate Hindu Emperor, or Samrajyapada. A second Tantric coronation followed shortly afterwards, which his followers believed gave him special access to the powers and blessings of three great goddesses of the Konkan mountains:

Sivaji entered the throne room with a sword and made blood sacrifices to the lokapalas, divinities who guard the worlds. The courtiers attending the ceremony were then asked to leave while auspicious mantras were installed on the king’s body to the accompaniment of music and the chanting of samans. Finally he mounted his lion throne, hailed by cries of ‘Victory’ from the audience. He empowered the throne with the mantras of the ten Vidyas. Through their power, a mighty splendour filled the throne-room. The Saktis held lamps in their hands and lustrated the king, who shone like Brahma.95

Aurangzeb dismissed Shivaji as a ‘desert rat’. But by the time of his death in 1680, Shivaji had turned himself into Aurangzeb’s nemesis, leaving behind him a name as the great symbol of Hindu resistance and revival after 500 years of Islamic rule. Within a generation, Maratha writers had turned him into a demi-god. In the Sivabharata of Kaviraja Paramananda, for example, Shivaji reveals himself to be none other than Vishnu-incarnate:

I am Lord Vishnu,

Essence of all gods,

Manifest on earth

To remove the world’s burden!

The Muslims are demons incarnate,

Arisen to flood the earth,

With their own religion.

Therefore I will destroy these demons

Who have taken the form of Muslims,

And I will spread the way of dharma fearlessly.96

For many years the Mughal army fought back steadily, taking one Deccan hillfort after another, and for a while it looked like the imperial forces were slowly succeeding in crushing Maratha resistance as methodically as they did that of the Company. On 11 March 1689, the same year that the Emperor crushed the Company, Aurangzeb’s armies captured Sambhaji, the eldest son and successor of Shivaji. The unfortunate prince was first humiliated by being forced to wear an absurd hat and being led into durbar on a camel. Then he was brutally tortured for a week. His eyes were stabbed out with nails. His tongue was cut out and his skin flayed with tiger claws before he was savagely put to death. The body was then thrown to the dogs while his head was stuffed with straw and sent on tour around the cities of the Deccan before being hung on the Delhi Gate.97 By 1700, the Emperor’s siege trains had taken the Maratha capital, Satara. It briefly seemed as if Aurangzeb had finally gained victory over the Marathas, and, as the great Mughal historian Ghulam Hussain Khan put it, ‘driven that restless nation from its own home and reduced it to taking shelter in skulking holes and in fastnesses’.98

But in his last years, Aurangzeb’s winning streak began to fail him. Avoiding pitched battles, the Marathas’ predatory cavalry armies adopted guerrilla tactics, attacking Mughal supply trains and leaving the slow, heavily encumbered Mughal columns to starve or else return, outmanoeuvred, to their base in Aurangabad. The Emperor marched personally to take fort after fort, only to see each lost immediately his back was turned. ‘So long as a single breath of this mortal life remains,’ he wrote, ‘there is no release from this labour and work.’99

The Mughal Empire had reached its widest extent yet, stretching from Kabul to the Carnatic, but there was suddenly disruption everywhere. Towards the end it was no longer just the Marathas: by the 1680s there was now in addition a growing insurgency in the imperial heartlands from peasant desertion and rebellion among the Jats of the Gangetic Doab and the Sikhs of the Punjab. Across the Empire, the landowning zamindar gentry were breaking into revolt and openly battling tax assessments and attempts by the Mughal state to penetrate rural areas and regulate matters that had previously been left to the discretion of hereditary local rulers. Banditry became endemic: in the mid-1690s the Italian traveller Giovanni Gemelli Careri complained that Mughal India did not offer travellers ‘safety from thieves’.100 Even Aurangzeb’s son Prince Akbar went over to the Rajputs and raised the standard of rebellion.

These different acts of resistance significantly diminished the flow of rents, customs and revenues to the exchequer, leading for the first time in Mughal history to a treasury struggling to pay for the costs of administering the Empire or provide salaries for its officials. As military expenses continued to climb, the cracks in the Mughal state widened into, first, fissures, then crevasses. According to a slightly later text, the Ahkam-i Alamgiri, the Emperor himself acknowledged ‘there is no province or district where the infidels have not raised a tumult, and since they are not chastised, they have established themselves everywhere. Most of the country has been rendered desolate and if any place is inhabited, the peasants have probably come to terms with the robbers.’101

On his deathbed, Aurangzeb acknowledged his failures in a sad and defeated letter to his son, Azam:

I came alone and I go as a stranger. The instant which has passed in power has left only sorrow behind it. I have not been the guardian and protector of the Empire. Life, so valuable, has been squandered in vain. God was in my heart but I could not see him. Life is transient. The past is gone and there is no hope for the future. The whole imperial army is like me: bewildered, perturbed, separated from God, quaking like quicksilver. I fear my punishment. Though I have a firm hope in God’s grace, yet for my deeds anxiety ever remains with me.102

Aurangzeb finally died on 20 February 1707. He was buried in a simple grave, open to the skies, not in Agra or in Delhi but at Khuldabad in the middle of the Deccan plateau he spent most of his adult life trying,103 and failing, to bring to heel. In the years that followed his death, the authority of the Mughal state began to dissolve, first in the Deccan and then, as the Maratha armies headed northwards under their great war leader Baji Rao, in larger and larger areas of central and western India, too.

Mughal succession disputes and a string of weak and powerless emperors exacerbated the sense of imperial crisis: three emperors were murdered (one was, in addition, first blinded with a hot needle); the mother of one ruler was strangled and the father of another forced off a precipice on his elephant. In the worst year of all, 1719, four different Emperors occupied the Peacock Throne in rapid succession. According to the Mughal historian Khair ud-Din Illahabadi, ‘The Emperor spent years – and fortunes – attempting to destroy the foundations of Maratha power, but this accursed tree could not be pulled up by the roots.’

From Babur to Aurangzeb, the Mughal monarchy of Hindustan had grown ever more powerful, but now there was war among his descendants each seeking to pull the other down. The monarch’s suspicious attitude towards his ministers and the commanders habitual interfering beyond their remit, with short-sighted selfishness and dishonesty, only made matters worse. Disorder and corruption no longer sought to hide themselves and the once peaceful realm of India became a lair of Anarchy.104

On the ground, this meant devastating Maratha raids, leaving those villages under Mughal authority little more than piles of smoking cinders. The ruthlessness and cruelty of these guerrilla raids were legendary. A European traveller passing out of Aurangabad came across the aftermath of one of these Maratha attacks:

When we reached the frontier, we found all put to fire and sword. We camped out next to villages reduced to ashes, an indescribably horrid and distressing scene of humans and domestic animals burned and lying scattered about. Women clutching their children in their arms, men contorted, as they had been overtaken by death, some with hands and feet charred, others with only the trunk of the body recognisable: hideous corpses, some char-grilled, others utterly calcined black: a sight of horror such as I had never seen before. In the three villages we passed through, there must have been some 600 such disfigured human bodies.105

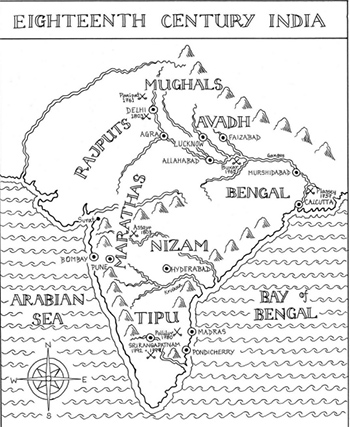

Yet if the Marathas were violent in war, they could in times of peace be mild rulers.106 Another French traveller noted, ‘The Marathas willingly ruin the land of their enemies with a truly detestable barbarity, but they faithfully maintain the peace with their allies, and in their own domains make agriculture and commerce flourish. When seen from the outside, this style of government is terrible, as the nation is naturally prone to brigandage; but seen from the inside, it is gentle and benevolent. The areas of India which have submitted to the Marathas are the happiest and most flourishing.’107 By the early eighteenth century, the Marathas had fanned out to control much of central and western India. They were organised under five chieftains who constituted the Maratha Confederacy. These five chiefs established hereditary families which ruled over five different regions. The Peshwa – a Persian term for Prime Minister that the Bahmani Sultans had introduced in the fourteenth century – controlled Maharashtra and was head of the Confederacy, keeping up an active correspondence with all his regional governors. Bhonsle was in charge of Orissa, Gaekwad controlled Gujarat, Holkar dominated in central India and Scindia was in command of a growing swathe of territory in Rajasthan and north India. The Marathas continued to use Mughal administrative procedures and practices, in most cases making the transition to their rule so smooth it was almost imperceptible.108

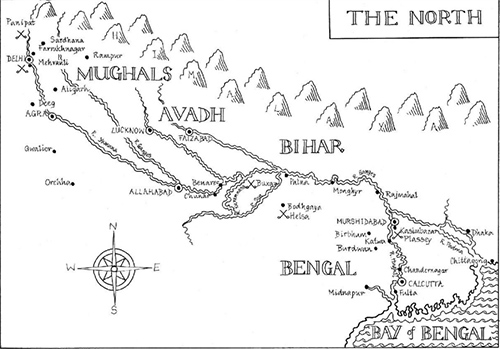

In the face of ever-growing Maratha power, Mughal regional governors were increasingly left to fend for themselves, and several of these began to behave as if they were indeed independent rulers. In 1724, one of Aurangzeb’s favourite generals and most cherished protégés, Chin Qilich Khan, Nizam ul-Mulk, left Delhi without the sanction of the young Emperor Muhammad Shah and set himself up as the regional Governor in the eastern Deccan, defeating the rival Governor appointed by the Emperor and building up his own power base in the city of Hyderabad. A similar process was under way in Avadh – roughly present-day Uttar Pradesh – where power was becoming concentrated in the hands of a Shia Persian immigrant, Nawab Sa’adat Khan, and his Nishapur-born nephew, son-in-law and eventual successor, Safdar Jung. Uncle and nephew became the main power brokers in the north, with their base at Faizabad in the heart of the Ganges plains.109

The association of both governors with the imperial court, and their personal loyalty to the Emperor, was increasingly effected on their own terms and in their own interests. They still operated under the carapace of the Mughal state, and used the name of the Emperor to invoke authority, but on the ground their regional governates began to feel more and more like self-governing provinces under their own independent lines of rulers. In the event both men would go on to found dynasties that dominated large areas of India for a hundred years.

The one partial exception to this pattern was Bengal, where the Governor, a former Brahmin slave who had been converted to Islam, Murshid Quli Khan, remained fiercely loyal to the Emperor, and continued annually to send to Delhi half a million sterling of the revenues of that rich province. By the 1720s Bengal was providing most of the revenues of the central government, and to maintain the flow of funds Murshid Quli Khan became notorious for the harshness of his tax-collecting regime. Defaulters among the local gentry would be summoned to the Governor’s eponymous new capital, Murshidabad, and there confined without food and drink. In winter, the Governor would order them to be stripped naked and doused with cold water. He then used to ‘suspend the zamindars by the heels, and bastinado [beat] them with a switch’. If this did not do the trick, defaulters would be thrown into a pit ‘which was filled with human excrement in such a state of putrefaction as to be full of worms, and the stench was so offensive, that it almost suffocated anyone who came near it … He also used to oblige them to wear long leather drawers, filled with live cats.’110

As the country grew increasingly anarchic, Murshid Quli Khan found innovative ways to get the annual tribute to Delhi. No longer did he send caravans of bullion guarded by battalions of armed men: the roads were now too disordered for that. Instead he used the credit networks of a family of Marwari Oswal Jain financiers, originally from Nagar in Jodhpur state, to whom in 1722 the Emperor had awarded the title the Jagat Seths, the Bankers of the World, as a hereditary distinction. Controlling the minting, collection and transfer of the revenues of the empire’s richest province, from their magnificent Murshidabad palace the Jagat Seths exercised influence and power that were second only to the Governor himself, and they soon came to achieve a reputation akin to that of the Rothschilds in nineteenth-century Europe. The historian Ghulam Hussain Khan believed that ‘their wealth was such that there is no mentioning it without seeming to exaggerate and to deal in extravagant fables’. A Bengali poet wrote: ‘As the Ganges pours its water into the sea by a hundred mouths, so wealth flowed into the treasury of the Seths.’111 Company commentators were equally dazzled: the historian Robert Orme, who knew Bengal intimately, described the then Jagat Seth as ‘the greatest shroff and banker in the known world’.112 Captain Fenwick, writing on the ‘affairs of Bengal in 1747–48’, referred to Mahtab Rai Jagat Seth as a ‘favourite of the Nabob and a greater Banker than all in Lombard Street [the banking district of the City of London] joined together’.113

From an early period, East India Company officials realised that the Jagat Seths were their natural allies in the disordered Indian political scene, and that their interests in most matters coincided. They also took regular and liberal advantage of the Jagat Seths’ credit facilities: between 1718 and 1730, the East India Company borrowed on average Rs400,000 annually from the firm.* In time, the alliance, ‘based on reciprocity and mutual advantage’ of these two financial giants, and the access these Marwari bankers gave the EIC to streams of Indian finance, would radically change the course of Indian history.114

In the absence of firm Mughal control, the East India Company also realised it could now enforce its will in a way that would have been impossible a generation earlier. Even in the last fraying years of Aurangzeb’s reign there had been signs that the Company was becoming less respectful of Mughal authority than it had once been. In 1701, Da’ud Khan, the Governor of the newly conquered Carnatic, complained about the lack of courtesy on the part of the Madras Council who, he said, treated him ‘in the most cavalier manner … They failed to reflect that they had enriched themselves in his country to a most extraordinary degree. He believed that they must have forgotten that he was General over the province of the Carnatic, and that since the fall of the Golconda kingdom they had rendered no account of their administration, good or bad … Nor had they accounted for the revenues from tobacco, betel, wine et cetera, which reached a considerable sum every year.’115

The Company’s emissary, Venetian adventurer Niccolao Manucci, who was now living as a doctor in Madras, replied that the EIC had transformed a sandy beach into a flourishing port; if Da’ud Khan was harsh and overtaxed them, the EIC would simply move its operations elsewhere. The losers would be the local weavers and merchants who earned his kingdom lakhs* of pagodas each year through trade with the foreigners. The tactic worked: Da’ud Khan backed off. In this way the EIC prefigured by 300 years the response of many modern corporates when faced with the regulating and taxation demands of the nation state: treat us with indulgence, they whisper, or we take our business elsewhere. It was certainly not the last time a ruler on this coastline would complain, like Da’ud Khan, that the ‘hat-wearers had drunk the wine of arrogance’.

Nine years later, the EIC went much further. In response to the seizure of two Englishmen and a short siege by the Mughal Qiladar (fort keeper) of Jinji, the factors of Fort St David, a little to the south of Madras, took up arms. In 1710, they rode out of their fortifications near Cuddalore, broke through Mughal lines and laid waste to fifty-two towns and villages along the Coromandel coast, killing innocent villagers and destroying fields of crops containing thousands of pagodas of rice awaiting harvest which, the Governor of Madras proudly reported, ‘exasperated the enemy beyond reconciliation’. This was perhaps the first major act of violence by Englishmen against the ordinary people of India. It was two years before the EIC was reconciled with the local Mughal government, through the friendly mediation of the French Governor of Pondicherry. The directors in London approved of the measures taken: ‘The natives there and elsewhere in India who have, or shall hear of it, will have a due impression made upon their minds of the English Courage and Conduct, and know that we were able to maintain a War against even so Potent a Prince.’116

In Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan had also become disgusted by the rudeness and bullying of the increasingly assertive Company officials in Calcutta and wrote to Delhi to make his feelings plain. ‘I am scarce able to recount to you the abominable practices of these people,’ he wrote.

When they first came to this country they petitioned the then government in a humble manner for the liberty to purchase a spot of ground to build a factory house upon, which was no sooner granted but they ran up a strong fort, surrounded it with a ditch which has communication with the river and mounted a great number of guns upon the walls. They have enticed several merchants and others to go and take protection under them and they collect a revenue which amounts to Rs100,000* … They rob and plunder and carry a great number of the king’s subjects of both sexes into slavery.117

By this time, however, officials in Delhi were occupied with more serious worries.

[x]

Delhi in 1737 had around 2 million inhabitants. Larger than London and Paris combined, it was still the most prosperous and magnificent city between Ottoman Istanbul and imperial Edo (Tokyo). As the Empire fell apart around it, it hung like an overripe mango, huge and inviting, yet clearly in decay, ready to fall and disintegrate.

Despite growing intrigue, dissension and revolt, the Emperor still ruled from the Red Fort over a vast territory. His court was the school of manners for the whole region, as well as the major centre for the Indo-Islamic arts. Visitors invariably regarded it as the greatest and most sophisticated city in South Asia: ‘Shahjahanabad was perfectly brilliant and heavily populated,’ wrote the traveller Murtaza Husain, who saw the city in 1731. ‘In the evening one could not move one gaz [yard] in Chandni Chowk or the Chowk of Sa’adullah Khan because of the great crowds of people.’ The courtier and intellectual Anand Ram Mukhlis described the city as being ‘like a cage of tumultuous nightingales’.118 According to the Mughal poet Hatim,

Delhi is not a city but a rose Garden,

Even its wastelands are more pleasing than an orchard.

Shy, beautiful women are the bloom of its bazaars,

Every corner adorned with greenery and elegant cypress trees.119

Ruling this rich, vulnerable empire was the effete Emperor Muhammad Shah – called Rangila, or Colourful, the Merry-Maker. He was an aesthete, much given to wearing ladies’ peshwaz and shoes embroidered with pearls; he was also a discerning patron of music and painting. It was Muhammad Shah who brought the sitar and the tabla out of the folk milieu and into his court. He also showered his patronage on the Mughal miniature atelier neglected by Aurangzeb and his successors, commissioning bucolic scenes of Mughal court life: the palace Holi celebrations bathed in fabulous washes of red and orange; scenes of the Emperor going hawking along the Yamuna or visiting his walled pleasure gardens; or, more rarely, holding audiences with his ministers amid the flowerbeds and parterres of the Red Fort.120

Muhammad Shah somehow managed to survive in power by the simple ruse of giving up any appearance of ruling: in the morning he watched partridge and elephant fights; in the afternoon he was entertained by jugglers, mime artists and conjurors. Politics he wisely left to his advisers and regents; and as his reign progressed, power ebbed gently away from Delhi, as the regional Nawabs began to take their own decisions on all important matters of politics, economics, internal security and self-defence.

‘This prince had been kept in the Salim-garh fort, living a soft and effeminate life,’ wrote the French traveller and mercenary Jean-Baptiste Gentil, ‘and now took the reins of government amid storms of chaos and disorder.’

He was young and lacked experience and so failed to notice that the imperial diadem he was wearing was none other than the head-band of a sacrificial animal, portending death. Nature lavished on him gentle manners and a peaceful character, but withheld that strength of character necessary in an absolute monarch – all the more necessary at a time when the grandees knew no law other than the survival of the fittest and no rule but that of might is right; and so this unhappy prince became the plaything, one after another, of all those who exercised authority in his name, who recognised that now-empty title, that shadow of a once august name, only when it served to legitimise their unlawful take-over of power. Thus in his reign, they carried out their criminal usurpations, dividing up the spoils of their unfortunate master, after destroying the remnants of his power.121

A French eyewitness, Joseph de Volton from Bar-le-Duc, wrote to the French Compagnie des Indes headquarters in Pondicherry giving his impressions of the growing crisis in the capital. According to a digest of his report:

the poor government of this empire seemed to prepare one for some coming catastrophe; the people were crushed under by the vexations of the grandees … [Muhammad Shah] is a prince of a spirit so feeble that it bordered on imbecility, solely occupied with his pleasures … The great Empire has been shaken since some time by diverse rebellions. The Marathas, a people of the Deccan who were at one time tributary, have shaken off the yoke, and they have even had the audacity to penetrate from one end of Hindustan in armed bodies, and to carry out a considerable pillage. The little resistance that they have encountered prefigures the facility with which anyone could seize hold of this Empire.122

De Volton was right: as the Maratha armies swept ever further north, even the capital ceased to be secure. On 8 April 1737, a swift-moving warband under the young star commander of the Maratha Confederacy, Baji Rao, raided the outskirts of Agra and two days later appeared at the gates of Delhi, looting and burning the suburban villages of Malcha, Tal Katora, Palam and Mehrauli, where the Marathas made their camp in the shadow of the Qu’tb Minar, the victory tower which marked the arrival of the first Islamic conquerors of India 600 years earlier. The raiders dispersed when news came that Nawab Sa’adat Khan was approaching with his army from Avadh to head them off; but it was nevertheless an unprecedented insult to the Mughals and a blow to both their credibility and self-confidence.123